dir. Chris Marker

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

52-week film challenge, film 46

I believe I am correct in saying that La jetée, at only 28 minutes long, is the shortest film in “Sight & Sound” magazine’s listing of the greatest films in history (currently ranked at #67 in the critics’ poll, but #35 in the directors’ poll). Nonetheless, its impact on the medium of film, on storytelling, and on the notion of “science fiction” is significant.

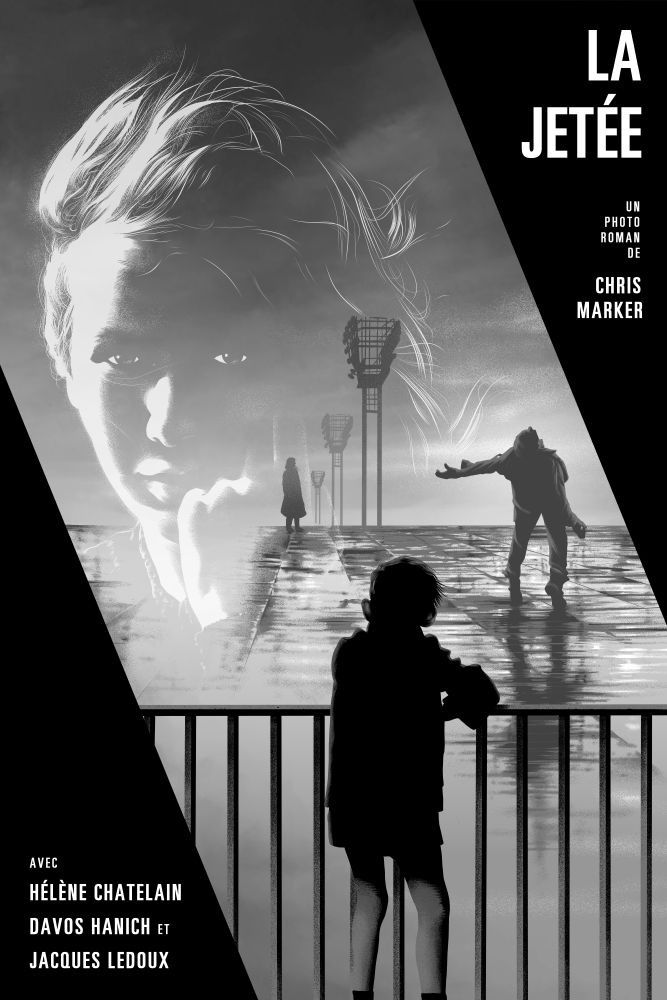

Some wag once called it “a slide show with an IQ of 180,” and they’re … not wrong. Except for a small moment of moving images, the film is composed almost entirely of photographic still images, where the viewer must study what’s briefly on screen carefully to extract as much information as possible, combining the visual information with the audio cues and narration. Of course the medium of film is itself a series of photographed still images, but show quickly enough that the illusion of movement, of synchronised sound, of emotion and performance, is fluid.

Here, director Marker slows down the flow to create an irony, rendering it as a unique method from which we get our information; we infer, rather than see, the passage of time between each image — that interesting process in our minds where our vague memories and our dreams cross each others’ paths.

The “story,” such as it is, is stark and minimal: in a bleak post-nuclear dystopia sometime after World War III, a man is selected by a small group of scientists (German, it seems, given the whispering that occasionally appears behind Jean Négroni’s vital and nearly poetic narration), to engage in an experiment to save the present by calling on the past and the future to provide a solution — induced psychological “time travel”

The man has always held some strong mental images to keep his memories intact, and these scientists can see into people’s minds, so they have picked him. While being held captive, he is injected with something to prompt his (mental) return to the past, before the current situation, where he meets a woman not unlike “The Time Traveller’s Wife” — a figure not part of his memories, who accepts each new visit without question, calls him “her ghost” and builds a bond of trust and friendship with him.

Having successfully sent him into the past, the scientist then attempt to send him into the future, with far more obscure results. The man, seduced by the woman of his “dreams,” appears to “escape” his present and live permanently within his memories with this woman — combining the hazy glow of happy memories with this new dream-like woman, forging his own personal paradise.

Despite the vagueness that is part and parcel of this story, there is a definite ending I won’t spoil. The narration acts as a hypnotic element drawing the viewer in alongside the score — the visuals, the narration, the score, and the still-image juxtaposition of past, present, and future all interplay with each other to create a remarkable journey that is likely to stay with viewers as they reassess their own recollections, dreams, and reality.

Yes, the Terry Gilliam film 12 Monkeys is something of an expanded and re-envisioned remake of La jetée, but I’d encourage anyone who hasn’t seen that (or even if they have) to sit with La jetée and let it mess with your own head a little bit.

Even the title is a bit of a mind-slip: Literally, it refers to the jetway at Orly airport (which we repeatedly come back to), but it’s been pointed out to me that the could be seen as a play on là j’étais, which translates to “there I was.”