Our David was a busy boy in the second half of 1973, with a bunch of different little projects going on in various directions — but no clear vision for what his next album would be, other than the song “1984” which he’d recorded in January of that year (a second version, “1984/Dodo” turned out to be his last-ever work with producer Ken Scott). He also had the ideas and some material created for “The 1980 Floor Show,” which was of course based on George Orwell’s seminal 1984 and had been kicking around pretty much since he’d started making albums under his own control.

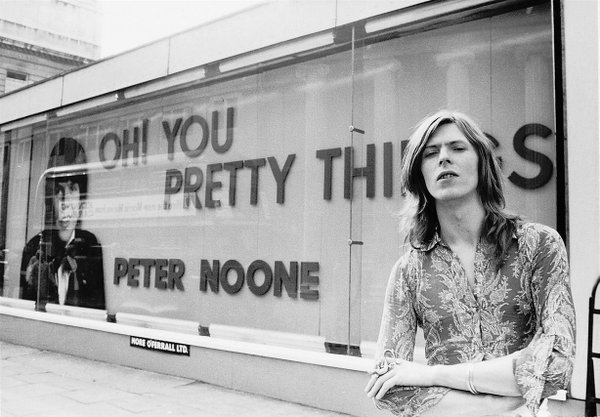

Scott moved over to work with Supertramp on Crime of the Century, while Bowie axeman Mick Ronson chose to start recording his own solo album, so I’m sure Bowie’s original plan was to just keep himself busy until (at least) Ronson would be available again, leaving an opportunity for a few notable side-trips. Among them were the ill-fated Astronettes album, “The Man Who Sold the World” single for Lulu, and a guest appearance on one track of Steeleye Span’s lovely Now We Are Six album. If you missed it, we took a deeper look at The Astronettes’ abandoned album here.

Bowie also turned down a request to produce Queen’s second album, and refused an offer to collaborate on a film version of the comic book series *Octobriana,* (which would have starred another girlfriend, Amanda Lear). There exists (allegedly) a demo for another song called “Star” (not the same as the one on Ziggy), which was said to have been written for Lear. Wait, though, we’re not done! He also entertained and had a recorded chat with Nova Express author William S. Burroughs (which would come out a year later in Rolling Stone) in which he first revealed he was trying out Burroughs’ “cut-up” technique for writing — in David’s case for lyrics and a potential Ziggy Stardust musical that would have scenes that could be presented in random order. He continued using the technique, off and on, for the decades.

Bowie also turned down a request to produce Queen’s second album, and refused an offer to collaborate on a film version of the comic book series *Octobriana,* (which would have starred another girlfriend, Amanda Lear). There exists (allegedly) a demo for another song called “Star” (not the same as the one on Ziggy), which was said to have been written for Lear. Wait, though, we’re not done! He also entertained and had a recorded chat with Nova Express author William S. Burroughs (which would come out a year later in Rolling Stone) in which he first revealed he was trying out Burroughs’ “cut-up” technique for writing — in David’s case for lyrics and a potential Ziggy Stardust musical that would have scenes that could be presented in random order. He continued using the technique, off and on, for the decades.

While only two new Ziggy-style songs came of that intriguing West End musical idea, by the winter Bowie had apparently decided instead to go with a television musical adaptation of 1984, and had already written a number of songs (or repurposed some older material) for that project. When Orwell’s widow turned down the 1984 idea, Bowie — in a process not unlike the creation of Nosferatu — decided to create his own “original” work which would just happen to have a very similar feel. The problem is, he wasn’t anywhere near focused enough to actually construct an entire show on this theme (which, barring direct evidence, we’ll put down to a combination of youthful distraction and his growing cocaine habit).

While an eventual staging was still on his mind (a number of drawn set ideas could be seen in the V&A “David Bowie Is” exhibit), the project ended up mostly flowing mostly into the first few minutes (and artwork) of Bowie’s studio album release for 1974, Diamond Dogs. Perhaps he would have created more material for the project (and the promising new persona of Halloween Jack) with more time, but Bowie was obligated to start touring again in the new year, so the record needed to get done and released. He salvaged what he could of the aborted 1984 material, threw in some Ziggy-type stuff to keep the kids happy, and stuffed it together into an extremely loose concept album (and this is one, barely) that definitely creates a mood, but falls more than a bit short on the narrative side.

While an eventual staging was still on his mind (a number of drawn set ideas could be seen in the V&A “David Bowie Is” exhibit), the project ended up mostly flowing mostly into the first few minutes (and artwork) of Bowie’s studio album release for 1974, Diamond Dogs. Perhaps he would have created more material for the project (and the promising new persona of Halloween Jack) with more time, but Bowie was obligated to start touring again in the new year, so the record needed to get done and released. He salvaged what he could of the aborted 1984 material, threw in some Ziggy-type stuff to keep the kids happy, and stuffed it together into an extremely loose concept album (and this is one, barely) that definitely creates a mood, but falls more than a bit short on the narrative side.

As Pegg notes, this ended up not being necessarily a bad thing. The rush to fill out the album ended up expanding Bowie’s repertoire rather considerably, added new funk and R&B elements he had been tinkering with via the Astronettes. Being unable to wait for Ronson to become available again, Bowie himself handled the guitar chores on the album, and he had to work with a new producer.

It also introduced his more mature lower-register singing voice — a new instrument only barely hinted at previously — and one which would play a very significant role in his later work. His basso profundo was a big influence later on for a number of other singers (most notably Peter Murphy). Taking on production duties himself as well, he was (at a guess) forced to make amends to Tony Visconti when it came time for string arrangements and mixing, since Bowie knew nobody better at it. This turned out to be a fortuitous event, as Visconti went on to work with Bowie for decades onwards.

Overall, Bowie’s willingness to push himself a ways out of his comfort zone (he would later say in interviews that he actually practiced guitar for several hours a day to prepare for recording) made for a more interesting record than the “soundtrack” to a non-existent stage show likely would have been — though if the track “1984” is an indication of what he might have done if he’d gotten the rights, his original vision and songs for that version of the show might have done quite well. As it is, the album hit #1 in the UK and Canada, and #5 in the US — though this was largely on the strength of the first single, “Rebel Rebel,” rather than the title track.

Diamond Dogs opens with an introduction to set the mood and fill in just enough story to set imaginations working. “Future Legend,” a heady mashup of George Orwell, William Burroughs, and Anthony Burgess, would absolutely have been the curtain-rising start of the theatrical show, though calling it a “song” stretches credibility a bit.

Diamond Dogs opens with an introduction to set the mood and fill in just enough story to set imaginations working. “Future Legend,” a heady mashup of George Orwell, William Burroughs, and Anthony Burgess, would absolutely have been the curtain-rising start of the theatrical show, though calling it a “song” stretches credibility a bit.

The sonic collage with narration paints a picture of a dystopian future New York City where “peoploids” roam and die upon the “slimy thoroughfare” while gangs of elite vampire thugs swing from the spires of Chase Manhattan Bank. It sounds (and looked like it would have looked like) a cross between Mad Max, A Clockwork Orange, Escape from New York and Lost Boys, all but one of which came out well after this record, but it would have been exceptionally tricky to realise on stage at the time. Someone (Bowie) can be heard playing “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” in the background, along with someone (Bowie) doing an impersonation of Scott Walker, alongside the sonic wall of sirens, dogs barking, children wailing and other such dystopian sounds.

It segues into the sound of a crowd cheering (stolen from a Faces album), and Bowie proclaiming “this ain’t rock ‘n’ roll … this is genocide!”, one of the most nihilistic rock calls ever. As if to prove his point, he immediately launches into his most blatantly Stones-influenced ripoff yet, the title track. From the melody to the arrangement, Mick and Keith would have had a very strong court case if they’d sued over the music, though the lyrics were rather a different (and darker) affair that save it from being pastiche. Even the humour in it was black as night: the opening stanza talks about the character having a “10-inch stump,” and seconds later mention he was “crawling down the alley on your hands and knee,” the singular “knee” — get it?

Bowie’s idea was that his burnt-out NYC gangs were kind of scavenger pimps-cum-Lord of the Flies in an anarchic ruin, left alone to do as they pleased — and what they pleased was to plunder the stores and bully the locals with a bit of ultraviolence. “When they pulled you out of the oxygen tent, you asked for the latest party” is another great opening line from David (and, years later, used visually for Screaming Lord Byron), and the song proceeds with considerable steam courtesy of all that ripping off of “It’s Only Rock and Roll.” Despite the strong opening gambit and catchy music, the song comes off the casual listener as just a considerably darker Stones number (and divorced of its context, that’s kinda what it is), and consequently as a single it didn’t do very well (by comparison with his recent successes), failing to crack the top 20 in the UK and not troubling the charts at all everywhere else.

Bowie’s idea was that his burnt-out NYC gangs were kind of scavenger pimps-cum-Lord of the Flies in an anarchic ruin, left alone to do as they pleased — and what they pleased was to plunder the stores and bully the locals with a bit of ultraviolence. “When they pulled you out of the oxygen tent, you asked for the latest party” is another great opening line from David (and, years later, used visually for Screaming Lord Byron), and the song proceeds with considerable steam courtesy of all that ripping off of “It’s Only Rock and Roll.” Despite the strong opening gambit and catchy music, the song comes off the casual listener as just a considerably darker Stones number (and divorced of its context, that’s kinda what it is), and consequently as a single it didn’t do very well (by comparison with his recent successes), failing to crack the top 20 in the UK and not troubling the charts at all everywhere else.

Many — including Bowie himself — have cast Diamond Dogs as being a harbinger of the punk movement that followed only a couple of years later. I’m more inclined to think that the same books and visuals that influenced Bowie along helped create punk, especially when combined with raging youth unemployment and a seemingly-uncaring government had more to do with it. Still, he gets credit for bringing those books’ and visuals into the rock arena first, and in a powerful way. As an album, I think Diamond Dogs was more of a breakup letter to/last hurrah for glam rock, and an embrace of concepts that would eventually evolve into Goth and New Romantic cultures.

But before we get to that, there’s one more “theatrical” movement to get through, the “Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (reprise)” suite. It’s a nice change-up, with the aforementioned R&B elements and his lower-register intro. There’s also an unusual but welcome Asian keyboard fill, courtesy of Mike Garson. The “Candidate” portion (which bears almost no resemblance to its original demo form, which was resurrected much later) harks back to — and is indeed pretty much the last echo of — the “stage show” idea, and the whole suite retains enough of the theatrical feel that listeners would be reminded that this is a concept album.

Then — out of nowhere — Side One ends with the goods: Bowie’s best-ever guitar lead (though he’s not the one performing it, ironically) and a powerful, poppy summing-up of his entire androgynous-glam-rocker milieu: “Rebel Rebel.” It was the natural choice for lead single, and pushed the album to the top of the charts all over the world. Bowie had proven he was more than Ziggy, ironically by calling up his ghost.

Side Two kicks off with a rather more Van Morrison-ish mid-tempo rocker, “Rock n Roll With Me,” a rare (to this point) co-written song; Bowie handled the lyrics and the chorus, while former Astronette (and school-age chum) Geoff MacCormack (going under the name Warren Peace) wrote the melody. It’s a bit reminiscent of Bill Withers’ 1972 hit “Lean on Me,” but rather more theatrical in Bowie’s hands as you might expect. Pegg notes that this song might originally have been written for the proposed musical based on the Ziggy album, though as with it being in Diamond Dogs there doesn’t seem to be any connection whatsoever to the claimed concept/story.

Listening to the album on CD as one does these days, the shot of adrenaline that was “Rebel Rebel” subsides and suddenly, the album takes a subdued and mildly soulful turn, with gentler tunes filled with introspective lyrics. When listening to the album on vinyl, of course, “Rebel” makes for a thrilling end of the first act, and the show must be rebuilt on Side Two to a finale and denouement. Heard in that way, the sequencing makes more sense than it does when you listen straight through.

“We Are the Dead” slows things down further, though it serves to start dragging us back to the original 1984 concept the album ostensibly represents — and indeed at one point “We Are The Dead” was to have been the album’s title. As a prelude to the restatement of the concept it starts off nicely, and sure enough once it fades out we are in full-on Issac Hayes mode with “1984,” which serves as the first half of the pinnacle of Act Two. If Bowie helped invent cyberpunk with JG Ballard (who, O’Leary notes, wrote a book about high-rise residents gone tribal that was published a year later) via “Diamond Dogs,” Visconti should get credit for helping popularize disco by going into a full-on disco Shaft-splosion with the string arrangements, adding a hell of a lot to the song compared to its two previous versions (from *The 1980 Floor Show* and a contemporary studio version), really giving life to the “plastic soul” concept that would emerge more fully in less than a year’s time.

The video below is a composite re-editing of the “1980 Floor Show” performance taken from rehearsals and outtakes in better quality, but gives you a much better feel both of the original performance and how different the songs were at this stage:

While Bowie was not the first to touch on “blue-eyed soul,” he certainly exploited and expanded on the efforts of his early influences and contemporaries, bringing rock back to its R&B roots as a replacement for glam — even if his execution at this point was sometimes a bit awkward (like the rather embarrassing album closer). Before that, though, we get a nearly Miles Davis-sequel opening for “Big Brother,” nicely segued from “1984” and continuing the excitement with bold, up-front lyrics and vocal fireworks, and a chorus (and some lyrics) seemingly “inspired by” the Bonzo Dog Band’s “Follow Mr Apollo.” It also features some Eno-esque synth work that foreshadows both his collaboration with Eno a few years to come, and the influence both this and those later records would have on a young Gary Numan.

Diamond Dogs is undoubtedly the most commercially successful return to Bowie’s Nietzchian obsession with false saviours and dystopian overlords that plays nicely with Orwell’s warnings, and makes it easy to see why Bowie was so attracted to the book in the first place: it’s a more visual, producible version of the saga of the ubermensch that Bowie has been reaching for since at least his third album. The track is nicely accentuated with trademark Bowie sax squonks, augmented horn works, and a chorale that shortly gives way to yet another “brother” segue before launching into a rather embarrassing (and culturally tone-deaf, if not downright insulting) tribal jam known as “Chant of the Ever Circling Skeletal Family” to lead us off stage and into that good night. The vinyl version originally ended with a looped “bruh”; the CD version mercifully fades this out quickly. Remember “Memory of a Free Festival” from Space Oddity? Something like that, but with a primitive — rather than hippie — vibe to it. Somebody who’d never heard it before and listened to it out of context might even think it was a bit racist, but in context the effect intended was clearly more about societal breakdown and devolution.

There are quite a few different versions of this album available now, with no less than three different remasterings. The first remastering was the 1990 Rykodisc/EMI release of the album, which features two bonus tracks: the rather retrograde “Dodo,” which was a standalone version re-recorded during the Diamond Dogs sessions, and a misnamed “demo” original version of “Candidate,” which except for a pair of re-used lyrics and the title is for all intents and purposes a completely different (and far, far better) song than its album namesake. For completists, “Dodo” appears to exist in four distinct versions, scattered among various reissues and other works.

“Dodo (You Didn’t Hear It From Me)” was originally intended as part of the original 1984 musical venture, and this is supported by its lyrics (with its references to children reporting their own parents to teh authorities). There was the version that appeared in “The 1980 Floor Show,” paired with an early version of “1984.” It was first recorded (the aforementioned last-ever work with Ken Scott) in late 1973, and languished in the vaults until it turned up on the 1989 Sound & Vision box set — a criminal act, as while the DD version of “1984” is more soulful, the version from ’73 is quite impressive in its own right.

“Dodo” was revamped and re-recorded as a standalone number during the Diamond Dogs sessions, intended to be a duet single with Lulu (and now part of the 1990 and 2004 Diamond Dogs CDs). Pegg believes the DD version was actually intended as a guide vocal for her, but there’s also the notion that Rykodisc simply removed Lulu’s possibly-recorded contribution from this version to avoid legal issues — based on the fact that a longer duet version actually exists with both performers present. That said, it seems like a demo rather than finished track, thanks to some distinctly lacklustre vocal performances. I remain unconvinced that if this single had ever been properly done released, it would have done about as well as previous Bowie/Lulu collaborations had done (i.e., not well), but “Dodo” on its own offers a very jaunty melody not a million miles from the alternate “Candidate,” and Bowie’s original take on the track is quite camp in tone, despite the rather dark lyrics.

The alternative “Candidate,” buoyed by some swinging Mike Garson piano and jaunty band action, actually finds the balance Bowie kept looking for between commercially-accessible music and Orwellian lyrics about messianic complexes, and would likely have been a hit single — had it made it onto the album. To think that it was buried in the vaults until this reissue in 1990 is almost criminal, particularly given the provocative and fascinating nature of the lyrics (“Inside every young pair of pants there’s a mountain,” just as an example).

The second remastering of the album was done at Abbey Road Studios in 1999 for an EMI/Virgin release with no bonus tracks). As your humble narrator doesn’t own this version, it’s outside the realm of this review to compare the second remastering to the first, though we’ve been told the 1999 one is “brighter” than the first.

The 30th Anniversary 2CD version (2004) nicely separates the original album and a mixed bag of related b-sides on a separate disc, the two bonus tracks already mentioned being among them. In addition, there is the 1973 studio versions of the “1984/Dodo” medley and the “Dodo” standa, a 1973 cover of Bruce Springsteen’s “Growin’ Up,” the wildly different 1974 “Rebel Rebel” US single version (with Geoff MacCormack on castanets and congas, a buried lead guitar line, and a tonne of other distractions and re-arranged pieces), a circa-2001 “Intimacy Mix” of the album version of “Candidate,” a 1980 “Best of K-Tel” edit (lopping over a minute off the album track!), and an interesting 2003 remake culled from the bonus tracks of Reality. If it were up to me, the two bonus tracks from the 1990 remaster, the 1973 studio recording of “1984/Dodo”, and that US single version of “Rebel” would be all that would be required to make what I would call a “definitive” version of the album.

The entire Diamond Dogs album was remastered yet again in 2016 as part of the Who Can I Be Now box set. The version there sounds terrific, but includes no bonus tracks per se, though there is an Australian radio edit of the “Diamond Dogs” single on another one of the discs in the set — a rarity never included before, but simply an edited version of the song. For those who want the best-sounding version of the original Diamond Dogs album, the box set one is the one you want (and that applies equally to the other albums covered in that set).

It is especially difficult to judge “I am a Laser,” the lead track on the original release. Bowie later reworked this into “Scream Like a Baby” on Scary Monsters, with all-new lyrics and vastly superior production for the latter version: the original is more sexually-oriented, making references to urination and “golden showers.” The third track, the Beach Boys standard “God Only Knows,” features a string arrangement by Tony Visconti, and closely resembles the version Bowie himself recorded two decades later for Tonight. On this first take, though, Cherry’s singing (and Visconti’s arrangement, including a sax solo from Bowie) provide more soul than the latter version.

It is especially difficult to judge “I am a Laser,” the lead track on the original release. Bowie later reworked this into “Scream Like a Baby” on Scary Monsters, with all-new lyrics and vastly superior production for the latter version: the original is more sexually-oriented, making references to urination and “golden showers.” The third track, the Beach Boys standard “God Only Knows,” features a string arrangement by Tony Visconti, and closely resembles the version Bowie himself recorded two decades later for Tonight. On this first take, though, Cherry’s singing (and Visconti’s arrangement, including a sax solo from Bowie) provide more soul than the latter version. Like Bowie himself at the time, the product is unfocused: while Cherry takes the lead about half the time, MacCormack and Guest handle vocals (and blend badly on occasion) the rest of the time, and the numbers without the benefit of Visconti’s gifted touch sound underdeveloped and rough. Complicating matters, there is a bootleg version of the original 11 numbers that claims to be directly from the original sessions, and features rather different takes.

Like Bowie himself at the time, the product is unfocused: while Cherry takes the lead about half the time, MacCormack and Guest handle vocals (and blend badly on occasion) the rest of the time, and the numbers without the benefit of Visconti’s gifted touch sound underdeveloped and rough. Complicating matters, there is a bootleg version of the original 11 numbers that claims to be directly from the original sessions, and features rather different takes.

This leads us into a brief return of David Bowie mk1, in the form of his cover of The Pink Floyd’s/Syd Barrett’s “See Emily Play,” very much the sort of music Bowie himself created in his first two albums. His take on it sounds like a fusion of the vocal style of his debut mixed with the backing band that created “The Man Who Sold the World.” Bowie backs himself up on Varispeed vocals to create a chorus of mental demons — he absolutely has a lot of empathy for the material and Syd, having had many mentally-ill relatives, the tragedy of his half-brother, his acquaintance with Barrett himself, and of course at this point in his life the madness of rock stardom. Garson again provides a lot of augmentation, while Ronson, Bolder, and Dunsbar create an arrangement significantly better than the original. The addition of strings at the end can, as O’Leary notes, be interpreted as the introduction of soothing medicine or a sign that the heroine of the song has completely withdrawn into her own troubled mind. It’s a great song made greater by Bowie, but it’s still rather jarring in the track mix, sandwiched as it is between the more typical “I Wish You Would” and the more typical rocker “Everything’s Alright.”

This leads us into a brief return of David Bowie mk1, in the form of his cover of The Pink Floyd’s/Syd Barrett’s “See Emily Play,” very much the sort of music Bowie himself created in his first two albums. His take on it sounds like a fusion of the vocal style of his debut mixed with the backing band that created “The Man Who Sold the World.” Bowie backs himself up on Varispeed vocals to create a chorus of mental demons — he absolutely has a lot of empathy for the material and Syd, having had many mentally-ill relatives, the tragedy of his half-brother, his acquaintance with Barrett himself, and of course at this point in his life the madness of rock stardom. Garson again provides a lot of augmentation, while Ronson, Bolder, and Dunsbar create an arrangement significantly better than the original. The addition of strings at the end can, as O’Leary notes, be interpreted as the introduction of soothing medicine or a sign that the heroine of the song has completely withdrawn into her own troubled mind. It’s a great song made greater by Bowie, but it’s still rather jarring in the track mix, sandwiched as it is between the more typical “I Wish You Would” and the more typical rocker “Everything’s Alright.”

The track — originally written by Bob Feldman, Jerry Goldstein, and songwriting legend Richard Gottehrer — was first recorded by the McCoys (who used it for a b-side in ’65) and then the Merseys (who had a big hit with it a year later). Despite being a cover, it seems both like a natural Bowie number as well as one for which he has some obvious affection. As Bowie discographer Nicholas Pegg notes, the arrangement makes it sound very much like something he’d have written for his pal Lulu, and adds that an ironic reissue of Bowie’s own “The Laughing Gnome” is said to have caused RCA to hold back the “Sorrow” single for a while (the “Laughing Gnome” re-release actually hit #6 on the UK charts, such as the popularity for anything with Bowie’s name on it by this point). Bowie’s version went on to become one of his most successful singles ever in terms of chart staying power; it lasted 15 weeks in the UK Top 40, peaking at #3.

The track — originally written by Bob Feldman, Jerry Goldstein, and songwriting legend Richard Gottehrer — was first recorded by the McCoys (who used it for a b-side in ’65) and then the Merseys (who had a big hit with it a year later). Despite being a cover, it seems both like a natural Bowie number as well as one for which he has some obvious affection. As Bowie discographer Nicholas Pegg notes, the arrangement makes it sound very much like something he’d have written for his pal Lulu, and adds that an ironic reissue of Bowie’s own “The Laughing Gnome” is said to have caused RCA to hold back the “Sorrow” single for a while (the “Laughing Gnome” re-release actually hit #6 on the UK charts, such as the popularity for anything with Bowie’s name on it by this point). Bowie’s version went on to become one of his most successful singles ever in terms of chart staying power; it lasted 15 weeks in the UK Top 40, peaking at #3.

Bowie’s skill at aping others also rears its head again: having done credible pastiches of Lou Reed and Marc Bolan (among others) on the last album, Aladdin Sane kicks off with an “homage” to the Rolling Stones, “Watch That Man.” It’s a straight-up rave-up designed rather cynically to catch the ear of both radios station programmers (back when humans did that job) as well as fans who climbed on board with Ziggy — not to mention a great way to start off the album.

Bowie’s skill at aping others also rears its head again: having done credible pastiches of Lou Reed and Marc Bolan (among others) on the last album, Aladdin Sane kicks off with an “homage” to the Rolling Stones, “Watch That Man.” It’s a straight-up rave-up designed rather cynically to catch the ear of both radios station programmers (back when humans did that job) as well as fans who climbed on board with Ziggy — not to mention a great way to start off the album. The third track is often hailed as Aladdin Sane’s highlight — and indeed it was one of Bowie’s biggest hits in the UK, rising to #3; it remained unissued as a single in the US, however (RCA oddly choosing “Time” instead), and as a result did not appear on any of Bowie’s greatest-hits compilations until the 1990s. Although this reviewer prefers “Cracked Actor” as his own favourite track, that song’s explicit balls-out lyric made it unsuitable for commercial release. Thus, it was Bowie’s pastiche/update to the 1950s songs of his youth, “Drive-In Saturday” — which still celebrates sex, but far more subtly through the device of a SF narrative where people have forgotten how to have it — made for a more suitable choice.

The third track is often hailed as Aladdin Sane’s highlight — and indeed it was one of Bowie’s biggest hits in the UK, rising to #3; it remained unissued as a single in the US, however (RCA oddly choosing “Time” instead), and as a result did not appear on any of Bowie’s greatest-hits compilations until the 1990s. Although this reviewer prefers “Cracked Actor” as his own favourite track, that song’s explicit balls-out lyric made it unsuitable for commercial release. Thus, it was Bowie’s pastiche/update to the 1950s songs of his youth, “Drive-In Saturday” — which still celebrates sex, but far more subtly through the device of a SF narrative where people have forgotten how to have it — made for a more suitable choice.

Still, almost as though asking for direct comparison, Bowie runs back to his faux-VU style to top his Stones cover with one of his own, and one of the best blues-rockers he ever did, “Jean Genie.” The whole band really comes together on this one, with bassist Bolder acknowledging the song’s origins as a Bo Diddley riff (from “I’m a Man”) by simply playing the original’s bass line. Ronson and Woodmansley keep close to the riff, allowing Bowie’s Reed-esque rhyming rap free range (and an interesting use of emphasis, with Bowie tending to lean on the penultimate syllable in each line rather than the last one).

Still, almost as though asking for direct comparison, Bowie runs back to his faux-VU style to top his Stones cover with one of his own, and one of the best blues-rockers he ever did, “Jean Genie.” The whole band really comes together on this one, with bassist Bolder acknowledging the song’s origins as a Bo Diddley riff (from “I’m a Man”) by simply playing the original’s bass line. Ronson and Woodmansley keep close to the riff, allowing Bowie’s Reed-esque rhyming rap free range (and an interesting use of emphasis, with Bowie tending to lean on the penultimate syllable in each line rather than the last one).

For this review, we used the 1999 EMI/Virgin version of the album, remastered by Peter Mew but keeping close to Ken Scott’s original production (just updated for modern systems more than anything else). If you’re into contemporaneous bonus tracks, the 2003 EMI/Virgin “30th Anniversary” release is the one you want, as it has the 1999 version but also includes an entire second disc of single versions (including the non-LP “John,” and a mono mix of “All the Young Dudes”), along with four live tracks from Boston Music Hall and one track from the Santa Monica gig later that same month, as well as one previously-unreleased live track from a Cleveland show that happened a month later. There is also a 40th anniversary release of the album proper (no bonus tracks), featuring a new remaster from AIR studios, but we’ve not had a chance to compare it to our 1999 version.

For this review, we used the 1999 EMI/Virgin version of the album, remastered by Peter Mew but keeping close to Ken Scott’s original production (just updated for modern systems more than anything else). If you’re into contemporaneous bonus tracks, the 2003 EMI/Virgin “30th Anniversary” release is the one you want, as it has the 1999 version but also includes an entire second disc of single versions (including the non-LP “John,” and a mono mix of “All the Young Dudes”), along with four live tracks from Boston Music Hall and one track from the Santa Monica gig later that same month, as well as one previously-unreleased live track from a Cleveland show that happened a month later. There is also a 40th anniversary release of the album proper (no bonus tracks), featuring a new remaster from AIR studios, but we’ve not had a chance to compare it to our 1999 version.

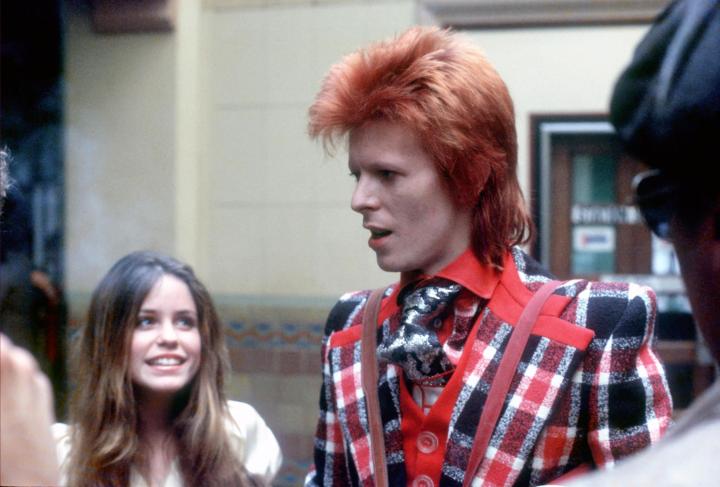

There have been a number of people credited for this major leap in both Bowie’s cohesion as a performer and songwriter; Iggy Pop, Marc Bolan, Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, and (notably) the influence of both the Legendary Stardust Cowboy and Vince Taylor. As usual, throw in what Bowie had recently been reading (especially Nietzsche and Crowley) and what he was reading or seeing just then (notably A Clockwork Orange and Quatermass, but also 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Who’s Tommy,and even Warhol’s Pork show), and his visits to the gay nightclub Sombrero with friend Freddie Buretti, Elton John (according to Elton) and others, then mix well. Gay and bisexual culture is quite prominent throughout Ziggy, and although “subtle” is not a word commonly associated with this album, the references largely (but not completely) fly under the radar for listeners who were already staunchly heterosexual.

There have been a number of people credited for this major leap in both Bowie’s cohesion as a performer and songwriter; Iggy Pop, Marc Bolan, Lou Reed, Andy Warhol, and (notably) the influence of both the Legendary Stardust Cowboy and Vince Taylor. As usual, throw in what Bowie had recently been reading (especially Nietzsche and Crowley) and what he was reading or seeing just then (notably A Clockwork Orange and Quatermass, but also 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Who’s Tommy,and even Warhol’s Pork show), and his visits to the gay nightclub Sombrero with friend Freddie Buretti, Elton John (according to Elton) and others, then mix well. Gay and bisexual culture is quite prominent throughout Ziggy, and although “subtle” is not a word commonly associated with this album, the references largely (but not completely) fly under the radar for listeners who were already staunchly heterosexual.

Having just put out a record with a completely new band that surprisingly dipped more than a toe into heavy metal, hard rock, and glam earlier in the year, Hunky Dory seems to be something of a throwback to gentler mainstream rock, with more than a few nods back to his hippie/folkie background. On the surface, the softer arrangements and highlighted piano leads might seem like a retreat from the bold (and occasionally exotic) Man Who Sold the World, but deeper listening shows evidence of lots of lessons learned from the foray into heavy guitar rock.

Having just put out a record with a completely new band that surprisingly dipped more than a toe into heavy metal, hard rock, and glam earlier in the year, Hunky Dory seems to be something of a throwback to gentler mainstream rock, with more than a few nods back to his hippie/folkie background. On the surface, the softer arrangements and highlighted piano leads might seem like a retreat from the bold (and occasionally exotic) Man Who Sold the World, but deeper listening shows evidence of lots of lessons learned from the foray into heavy guitar rock.

The lyric for “Warhol” is sublime and cutting; the man himself reportedly disliked it a great deal, but that’s only because the observation Bowie had hit the nail on the head. Bowie himself was a fan of the artist, and had hung out with many of Warhol’s gang when they were doing the Pork show in London (Angela was apparently a big fan). Oddly, Bowie and Warhol never really developed a friendship, though they cordially met several times and Bowie did a “screen test” for Warhol. Bowie later portrayed Andy (again with uncanny accuracy, killer vocal impression, and one of Andy’s actual wigs) in the film Basquiat. Funnily enough, Bowie apparently wrote the song intended for his friend Dana Gillespie to sing (which she did, though it wasn’t released until three years later on a hit album).

The lyric for “Warhol” is sublime and cutting; the man himself reportedly disliked it a great deal, but that’s only because the observation Bowie had hit the nail on the head. Bowie himself was a fan of the artist, and had hung out with many of Warhol’s gang when they were doing the Pork show in London (Angela was apparently a big fan). Oddly, Bowie and Warhol never really developed a friendship, though they cordially met several times and Bowie did a “screen test” for Warhol. Bowie later portrayed Andy (again with uncanny accuracy, killer vocal impression, and one of Andy’s actual wigs) in the film Basquiat. Funnily enough, Bowie apparently wrote the song intended for his friend Dana Gillespie to sing (which she did, though it wasn’t released until three years later on a hit album).

The best version of the album remains the 1990 EMI reissue, which restores the overly-cloying and oddly-exaggerated “Bombers” (apparently meant to be something of a … let’s say tribute … to Neil Young), the song was originally planned to open side two of the album, but dropped in favor of “Fill Your Heart.” In hindsight, it was best that it be left off, as it didn’t really fit the album: the music-hall style performance reminds one of something from the Love You Till Tuesday period, but with more mood-altering substances).

The best version of the album remains the 1990 EMI reissue, which restores the overly-cloying and oddly-exaggerated “Bombers” (apparently meant to be something of a … let’s say tribute … to Neil Young), the song was originally planned to open side two of the album, but dropped in favor of “Fill Your Heart.” In hindsight, it was best that it be left off, as it didn’t really fit the album: the music-hall style performance reminds one of something from the Love You Till Tuesday period, but with more mood-altering substances).

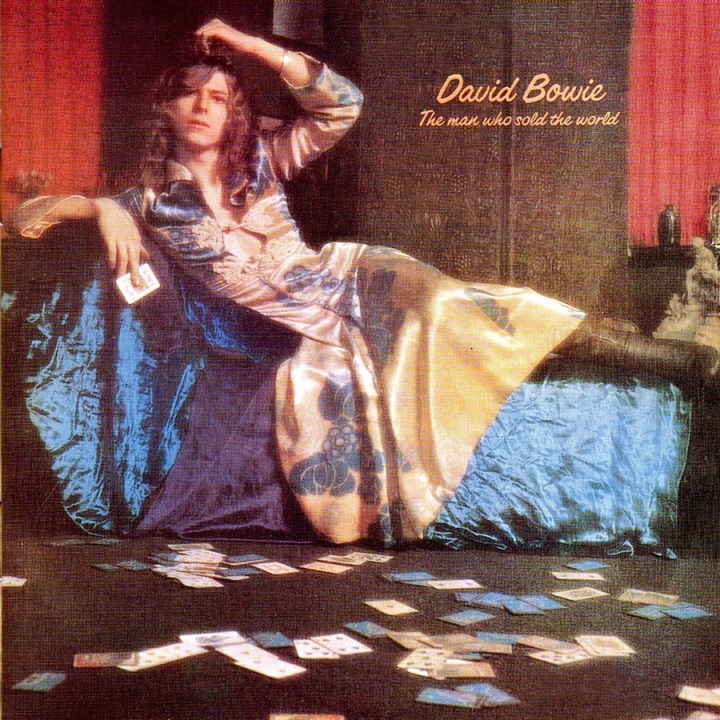

It’s difficult to track down any definitive evidence of Bowie’s own self-proclaimed bisexuality, but this reviewer has no trouble believing that — in his early years at least — he was. Lindsey Kemp has said he had a relationship with Bowie, Angie says David and Mick Jagger fooled around, Angie and David were both friends with gay designer Freddie Buretti (who lived with him and Angie at Haddon Hall for a while), they hung out with loads of other gay people, and Angie was another self-proclaimed bisexual. Despite any homosexual acts being prosecutable in the UK at the time, and despite Bowie’s later seeming exclusivity with women, there’s a handful of people who say Bowie was at least willing to experiment. It is undeniable that he found gay culture at the very least fashionable and fun — there’s a fair amount of polare and other gay slang littered amongst his early-70s work, and then there’s that dress and the long hair and the beginning of the gender blurring.

It’s difficult to track down any definitive evidence of Bowie’s own self-proclaimed bisexuality, but this reviewer has no trouble believing that — in his early years at least — he was. Lindsey Kemp has said he had a relationship with Bowie, Angie says David and Mick Jagger fooled around, Angie and David were both friends with gay designer Freddie Buretti (who lived with him and Angie at Haddon Hall for a while), they hung out with loads of other gay people, and Angie was another self-proclaimed bisexual. Despite any homosexual acts being prosecutable in the UK at the time, and despite Bowie’s later seeming exclusivity with women, there’s a handful of people who say Bowie was at least willing to experiment. It is undeniable that he found gay culture at the very least fashionable and fun — there’s a fair amount of polare and other gay slang littered amongst his early-70s work, and then there’s that dress and the long hair and the beginning of the gender blurring.

To really understand this second album, it occurs to me that the hidden context is crucially important. No less than five major negative events occurred between the release of the previous album and the one now most commonly known as Space Oddity, and they reshaped Bowie in several ways. The first was having his debut album not do well and, despite recording some interesting (and more commercial) new songs for a planned second album, his label dropping him. This, on the heels of his unsuccessful singles, must have been a difficult blow. It was followed in rapid succession by more tragedies: his first real love left him (though it was, as he later admitted, his own fault); his delvings into hippie culture and creating an arts community didn’t pan out to his satisfaction; he split with influential manager Ken Pitt; and his father Haywood Jones, who had been supportive of his artistic efforts, died rather unexpectedly.

To really understand this second album, it occurs to me that the hidden context is crucially important. No less than five major negative events occurred between the release of the previous album and the one now most commonly known as Space Oddity, and they reshaped Bowie in several ways. The first was having his debut album not do well and, despite recording some interesting (and more commercial) new songs for a planned second album, his label dropping him. This, on the heels of his unsuccessful singles, must have been a difficult blow. It was followed in rapid succession by more tragedies: his first real love left him (though it was, as he later admitted, his own fault); his delvings into hippie culture and creating an arts community didn’t pan out to his satisfaction; he split with influential manager Ken Pitt; and his father Haywood Jones, who had been supportive of his artistic efforts, died rather unexpectedly.

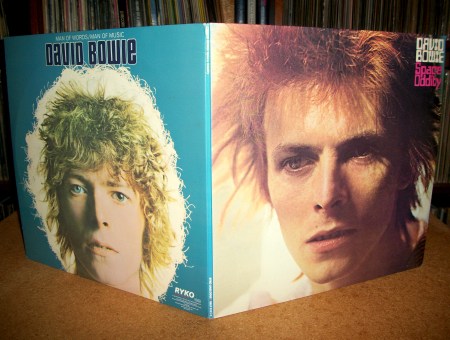

That his hair seems to have “exploded” both on the Phillips/Mercury original and more punk-looking RCA cover (where he looks for all the world like a young John Lydon) is oddly symbolic of the growth of both his mind and talent, and the UK cover was a strong visual indicator of the hippie style he had now fully embraced rather than just flirted with. As it turns out, it was a blessing in disguise that Bowie’s first album didn’t do well; had it done, he would have been unlikely to follow some of the various paths he eventually took, becoming more of a conventional and “pleasant” pop star in the mold of a Barry Manilow or Neil Diamond (though undoubtedly a bit darker and odder than either; imagine an entire career similar to the work he did in Labyrinth).

That his hair seems to have “exploded” both on the Phillips/Mercury original and more punk-looking RCA cover (where he looks for all the world like a young John Lydon) is oddly symbolic of the growth of both his mind and talent, and the UK cover was a strong visual indicator of the hippie style he had now fully embraced rather than just flirted with. As it turns out, it was a blessing in disguise that Bowie’s first album didn’t do well; had it done, he would have been unlikely to follow some of the various paths he eventually took, becoming more of a conventional and “pleasant” pop star in the mold of a Barry Manilow or Neil Diamond (though undoubtedly a bit darker and odder than either; imagine an entire career similar to the work he did in Labyrinth).

For the purposes of this review, we are using just the first half of the two-CD David Bowie: Deluxe Edition set that includes an entire second disc of material, including single and alternate versions of LP songs, non-LP a- and b-sides, and even a few songs intended for a second Deram album that never ended up happening. The first disc has both the stereo and mono versions of David Bowie as released on 1-June 1967 (indeed, it was one of the first to get both a stereo and mono release in the pop genre) and while there are very minor differences between them, they are essentially equivalent for all but the nit-pickiest of listeners. The deluxe release is highly recommended for its rich supplementary material and the definitive remasterings of the original album mixes. It is truly the alpha and omega of Bowie’s Deram period, and expands what was going on with the still very much developing songwriter and singer beyond what the original album release imparted.

For the purposes of this review, we are using just the first half of the two-CD David Bowie: Deluxe Edition set that includes an entire second disc of material, including single and alternate versions of LP songs, non-LP a- and b-sides, and even a few songs intended for a second Deram album that never ended up happening. The first disc has both the stereo and mono versions of David Bowie as released on 1-June 1967 (indeed, it was one of the first to get both a stereo and mono release in the pop genre) and while there are very minor differences between them, they are essentially equivalent for all but the nit-pickiest of listeners. The deluxe release is highly recommended for its rich supplementary material and the definitive remasterings of the original album mixes. It is truly the alpha and omega of Bowie’s Deram period, and expands what was going on with the still very much developing songwriter and singer beyond what the original album release imparted.