Director: George Dunning

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

I’ve seen this film quite a number of times in my life, but until now I haven’t written about it because I still think of its as a “kid’s movie,” since I first saw it as a child myself. My affection for it meant I bought the DVD release when that came out in 1999, though I haven’t yet gotten (and should get) the later 4K/Blu-Ray version at some point.

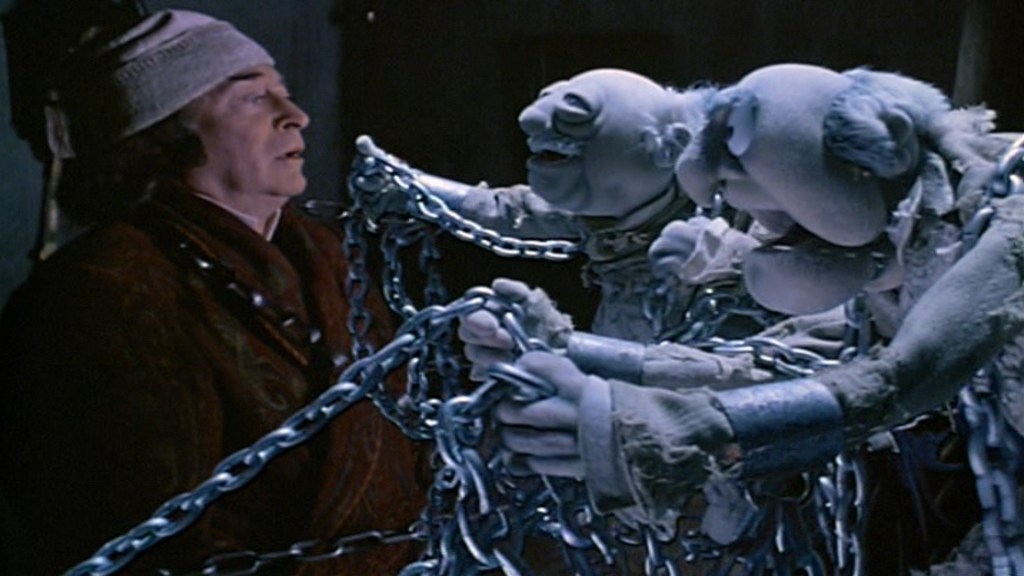

The adult in me is always, always disappointed that the Beatles themselves did not play a bigger role in the film, though they do appear in a short and kind of awkward live-action sequence at the very end — and of course those are their real voices in all the songs. Voice actors portrayed them in all the film’s dialogue for some reason, though the impersonators do a credible enough job making the four Liverpudlians sound (mostly) distinct from each other.

John Clive portrayed John Lennon’s speaking voice, and Geoffrey Hughes played Paul McCartney pretty accurately. A completely uncredited Paul Batten did most of George Harrison’s voice.

There’s a reason Batten didn’t complete his role in the film, or get credited for it — midway through it, he was arrested for being a deserter from the British Army!

Special kudos to Paul Angelis for his very spot-on Ringo — he (unlike most of the other voice actors) played multiple roles, including the narrator, and the Chief Blue Meanie, with great variety — and following Batten’s arrest, Angelis took on the rest of the George Harrison dubbing as well.

Comedian Dick Emory was the only other actor to voice multiple roles (he did Max, the Lord Mayor, and the principal add-on character of Jeremy Hillary Boob, who acts as a kind of guide through the adventure. As near as I can tell, he’s the only main character entirely original to the film, in the sense of the fact that he’s not inspired by or referenced by any Beatles lyric.

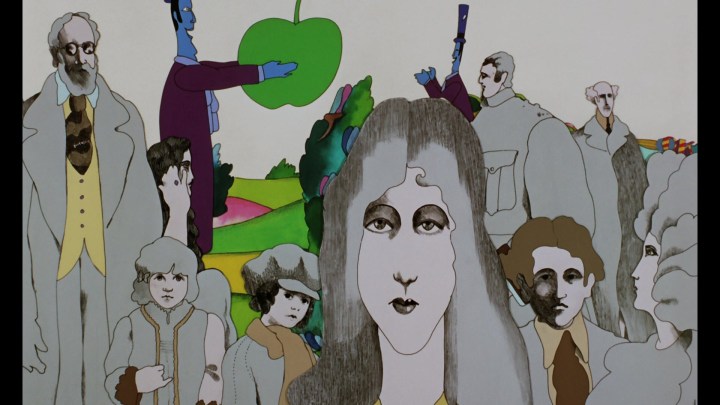

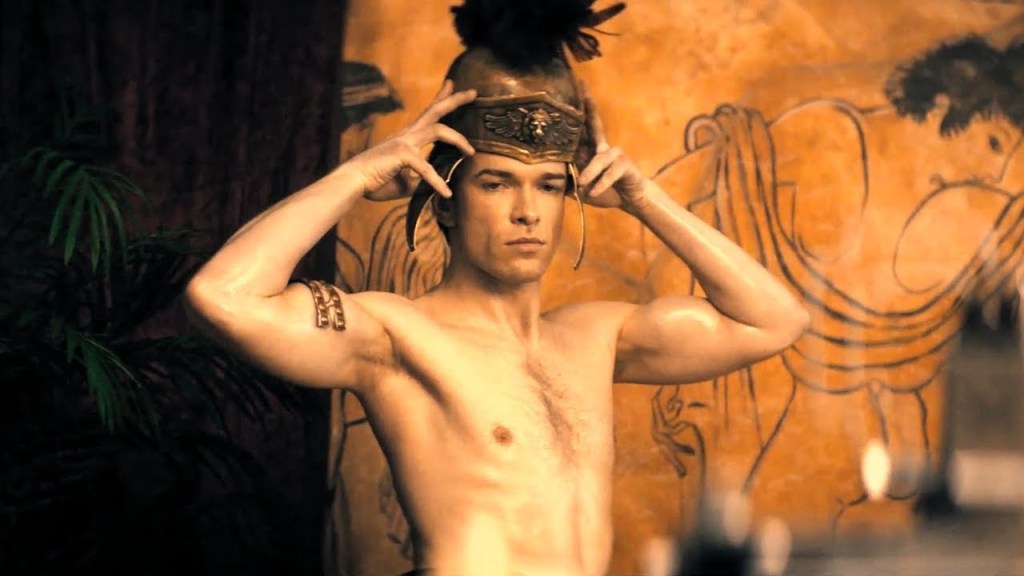

The unique animation of the film is very influenced by Peter Max and the general mod/psychedelic tone of the late 60s, but I was suprised to later learn that Max actually had nothing to do with the film. Looking at the artwork now, it’s an obvious influence of course — but not up to the standards of Max’s print work.

The 1999 DVD release boasts “frame by frame hand restoration” and does indeed look terrific. It also included a 5.1 surround sound remix, as well as the original stereo and mono audio as options. The version I have also offered reproduction film cells, stickers, and an expanded booklet — the latter featuring an introduction by Disney and Pixar’s John Lassiter.

Lassiter points out that the mixed-media animation of Yellow Submarine undoubtedly was influenced by then-recent UK immigrant Terry Gilliam, who brought his style of mixed-media animation to early shows like “Do Not Adjust Your Set” before ending up in “Monty Python’s Flying Circus.” The images in Yellow Submarine subsequently influenced cartoons for US kid’s shows like “Sesame Street” and “The Electric Company,” and even “Schoolhouse Rock.”

As for the film itself: what it lacks in plot complexity, it more than makes up for with this visual feast. The rich imagination and style of the original characters in “Pepperland,” from the Lonely Hearts Club Band to the supporting characters of Sgt. Pepper, Old Fred, the Blue Meanies, the Apple Bonkers, and the helpful Jeremy Boob are all interesting enough to keep the film moving along between musical numbers.

It might have been good to not have so much of the film’s background be completely white, but I guess they opted to put the main artwork front and center — to say nothing of saving money on background animators.

That’s not to say the backgrounds aren’t imaginative, such as the Sea of Holes and the Sea of Science (among others), which do a good job holding viewers’ attention across the thin plot. There’s even time for a classic “hall of doors” comedy bit during one of the numerous musical numbers.

It is helpful to bear in mind when watching the film that much of this Beatles music would have been brand new or very recently released to the original cinema audience and fans of the band, including “Only a Northern Song,” “Hey Bulldog.” Of course, the foundational musical score outside of the songs came from George Martin, and remains excellent and memorable as his soundtrack work generally is.

Some of the best animation takes place at the beginning and end of the film: the population of Pepperland being attacked and frozen, drained of all colour — and the restoration of Pepperland at the conclusion. The plot, such as it is, is that the Blue Meanies decide to be evil and come over the hill to steal all the music that brings joy to the people of Pepperland.

They starting by attacking Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, the main source of the music there. The incredibly elderly Lord High Mayor sends his lieutenant, Old Fred, to get help.

Fred manages to outrun the Meanies, commandeering the handy artifact of the Yellow Submarine, and travels through strange lands before coming across the Beatles, whom he persuades to help him.

They cross those and other “lands” in trying to return to Pepperland, with occasional stops to explore. Once back in Pepperland, our heroes evade the Meanies and Bonkers before the Beatles can finally take the place of the original Sgt. Pepper’s band, using their own music to unfreeze Pepperland and defeat its enemies and restore the original Lonely Hearts Club band.

By today’s pacing standards, some viewers will feel it a bit drawn out (which it is). However, if you appreciate the Beatles’ late-60s output and the changes the band itself was going through, watching the beautiful artwork (still like no other animation I can think of) and listening to the songs will help the 90-minute length go by pleasurably.

It remains a unique film, both in the history of animated films and as the only non-live action Beatles movie. It also remains effective as a time capsule of a short moment in history where this look, sound, and style was all the rage.

Yellow Submarine reminds me a lot of episodes of TV comedy “Laugh-In,” which adopted a very similar look and feel for its whimsical and fashionable late-60s comedy show.

You never knew what was going to happen next in that TV show, and likewise you mostly don’t know what you’ll be seeing next in Yellow Submarine. There are some 17 (!) Beatles songs heard in whole or in part, so if you are one of the few that really don’t like the Beatles’ music, this film is most definitely not for you.

For everyone else, more than five decades after its original release, it’s a musical and visual treat that blends fab (four) pop-rock tunes and simple but stylish animation to make for a pleasant animated adventure musical. The fact that there’s (still!) nothing else much like it all these years later is a testament to the originality of the approach.

If the Beatles had done their own voices for the dialogue, I’d have rated it the second-best of the Beatles’ five-film music career, with number one being their whimsical debut A Hard Day’s Night, which I reviewed in 2023.

Sadly they didn’t, so I think it gets knocked down to third place, with the uneven but wonderfully weird Magical Mystery Tour in second (for me), the straight performance film and breakup documentary Let It Be in fourth, and the witless Help! a nearly-undisputed clunker at the bottom of the list.