Or, why The Force Awakens is fun but will ultimately make you angry

I want you to see the new film Star Wars: The Force Awakens (also known as Episode VII). I want everyone to see it. If you’re looking for a light, fun, space-adventure movie to see on the big screen, you’re not going to find anything better. It is a visual treat on many levels, it brings some great new elements into the larger story, and of course it is wonderful to see some of the characters from the first Star Wars movie back again. I’m sure you’ll enjoy it, so go see it, particularly in IMAX if you can.

Just don’t think about it too much afterwards.

Obviously, from here on in we will be mentioning all kinds of spoilers (both plot developments and insights that will ruin some of the film for you). So please, I’m asking you nicely and seriously, stop reading this if you haven’t seen the film. This analysis is for people who have seen it and would like more insight into where the story does and doesn’t work: it will annoy the crap out of you if you read this first and watch the film afterwards. So don’t.

The TL;DR version of the critique is that although the film is executed very well and the new elements are welcome, the story is almost a play-for-play remake of A New Hope (the first of the Star Wars films, also known as Episode IV), only with some light twists (nothing wrong with that) that depend greatly on utterly ridiculous coincidences, character decisions, and filmmaker choices. So in short, it’s very much like Star Trek: Into Darkness in its interior badness. Because the film is very fast-paced, visually exciting, and has lots of explosions and fights, even serious fans will probably not notice this on first viewing, because the film is genuinely fun and cleverly made — and we also said this exact same thing about Into Darkness: it’s eye candy and then it grows increasingly silly until you’re finally angry at how completely empty the movie actually is.

Let us start, however, with those things that rightly deserve praise, because they do, and because nobody likes a wet blanket who can only talk about the problems with something and not acknowledge the good things. It was great to see some interesting new characters, major and minor, and while there are some questions lingering over Rey that hopefully will get answers in the future films (like “if she’s supposedly Luke’s kid, why has she got a British accent?”), but I have nothing but praise for her performance. Likewise, I thought the idea of showing that Stormtroopers are real people and can have changes of heart was an intriguing idea (yes, I know this was explored in other media, but I’m limiting myself to someone who mainly knows the Star Wars saga through the movies), and I thought John Boyega’s casting was fresh and good.

I’m unsure how to judge the characters Poe Dameron (Oscar Issac) and Kylo Ren (Adam Driver) just yet, since their characters are clearly going to be developed further, but my initial impression is that Poe is (sorry) kind of a two-dimensional and all-good mix of Luke and Han, Finn is a mix of pre-A New Hope Han Solo and A New Hope-era Luke, Rey is a mix of Luke and Leia and Chewbacca (yes, you heard me), while Kylo is a remix of Prequels Anakin and Empire Strikes Back-era moral-quandry Luke. I’ve rarely had an issue with the casting in JJ Abrams’ movies, apart from Chris Pine, so his continuing the tradition of adding some unknowns was a great move (as it was when Lucas did it the first time around), and they’re all interesting choices and a good mix. Simon Pegg’s disguised cameo as Unkar Plutt was delightful — I often wish we got a bit more time and story on these interesting minor characters.

Since it is heavily stolen from A New Hope with elements of The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi (and even a bit of the Prequels) thrown in, the story is naturally fun and exciting — a lot of older fans have said “it made me feel like I was 10 years old again,” or however old they were in 1977, which isn’t surprising since it is little more than a remix of that movie. That said, of course we’re thrilled to see the original characters, major and minor, and of course we’re pleased to see the effects updated to modern standards but otherwise left un-messed with. I thought the effects throughout were just great, including the mix of physical and CGI effects, the nice use of 3D in the 3D version (present, but not overused, and for once not dimming of the film overall), the expansiveness of the IMAX version, and the effectiveness of the music.

You can even get the film in a “D-box” version that rattles your seat when explosions happen, and jerk you around in the battle scenes, or the whole triple-play (3D/IMAX/D-box) if you shell out enough. I haven’t seen the “ordinary” non-IMAX 2D version yet, so I can’t judge on that, but I’d bet it loses none of the emotional or visual thrills for it. As I said at the top, if you’re just going to this movie for fun and thrills, it’s great. You won’t be disappointed — unless you wanted something substantive, because there isn’t that much here for people who care deeply about the entire saga, but there’s a lot of resonance for people who only remember Episode IV from their youth. A ton of it, and it’s not unwelcome at all.

It’s only when you start to think about it — like the recent Star Trek, or Star Trek: Into Darkness — that it starts to fall apart, and you realize the Emperor — sorry, Supreme Leader — barely has a stitch on. I’ve seen some other criticisms of the film harsher than this one will be, such as “40 Unforgivable Plot Holes in The Force Awakens” (which was followed up with another 20 additional problems, by the way!) — but about half of these are either subtle stuff he missed, or will probably (I say “probably” because you can’t trust JJ Abrams on this at all) be addressed later, or weren’t really either plot holes or unforgivable.

Still, most of the critics of the film I’ve read are more right than wrong — there’s nothing wrong with some homage to what came before, particularly at this point, but Abrams just went waaaay beyond that point into cribbing A New Hope wholesale, which ultimately makes The Force Awakens not fit in the saga at all. Say whatever you like about the three Prequel films, and believe me I did not enjoy them, but they did in fact add to the unfolding story. You can summarize the first six films by saying “there was a boy who was strong in the force and was eventually turned to the dark side, and as a man became the face of the Empire, but his son and daughter, led by a former mentor of the boy and a friendly but rogue stranger, teamed up to defeat the evil Empire and stop the mass slaughter of billions of freedom-loving people … and then, in Episode VII, they did that again.”

The Force Awakens doesn’t really advance the plot: it rehashes Episode IV in a sort of re-telling that appears, at the end of the day, only to exist to hand off the lead roles to some new people and bring casual people up to speed on where we are (which, this being a sequel to a 1983 movie, was important — but it’s all that’s here, with precious little actual new content).

Here’s what happened in the (let’s say) 25 years since Episode VI, since Episode VII is supposed to follow it: following a presumed period of peace, the New Republic (which is good, mostly, but seems ambiguous in the new film) have been running things, and the Republicans (sorry, the Empire — no, ’scuse me, the First Order) have sprung up and are fighting the New Republic (why? No reason given, sorry). For reasons also not mentioned or even hinted at, the New Republic has decided to fund a group of rebels (sorry, Resistance) within the systems controlled by the First Order to fight against them, and the First Order’s reaction is — in a stunning lack of imagination — to yet again (third time!) build a new Death Star (sorry, Death Planet — it’s bigger!) to destroy the Resistance and New Republic, and murder billions of apolitical innocents. Cuz righteousness, or … well, as I say, don’t think about it too much.

Han and Leia have split up because their son, Ben Solo, turned to the Dark Side of the Force, having previously been “the strongest in the Force we’ve ever seen,” at least since the last “strongest in the Force we’ve ever seen,” Anakin Skywalker — Ben’s grandfather, and of course the former Darth Vader. Luke, who was training Ben, was so devastated when he went bad and murdered the other students that he has spent several years (let’s say five?) years in hiding, doing absolutely nothing, it would seem. When we finally see him, he is literally doing nothing at all.

Ben has taken the name Kylo Ren and is now a slave of the Emperor, sorry Supreme Leader Snoke, and is a very high-up in the Empire (dammit, sorry, First Order) during this very short period (but let it slide, that’s not an unforgivable plot hole). Luke may have also abandoned his daughter (Rey, perhaps, we don’t know for sure but seems obvious) when she was around four years old to go take off somewhere for some reason, or maybe (likely) to protect her because she was so strong in the Force and he didn’t want the First Order to find her. Seems kinda harsh, but let’s reserve judgement on that, as that’s essentially what Obi-Wan did to Luke and Leia. C-3PO got a red arm and sounds kinda funny now, and R2-D2 has been in low-power mode since Luke left him behind following the massacre of his students, and will only awaken when the plot demands it — since he just happens to have the rest of the map they need to find Luke.

Han reacted to this situation by running away from it, rejoining with Chewbacca to go back to being a dodgy-but-lovable rogue smuggler (violating the laws of … the Republic? The First Order? Not clear) and Chewbacca seems completely unaffected by the passage of time (indeed, he’s gotten spritelier it would seem!). Leia has returned to being a General and leader of the Reb– sorry, Resistance, along with a bunch of old Rebel characters.

Interestingly, at least to those of us who found the backstory alluded to in the early Star Wars films, and fleshed out quite a bit in the Prequels about the only interesting thing in those three later films, there’s been a lot of political changes going on in the background that leads up to Episode VII, but sadly we get too little information about it; a clever fellow at Vox has put together a really good summary that actually adds to, rather than detracts from or spoils, the new film, and if you’re interested in that aspect of the story you should read it.

In the actual film, it just ends up being the Empire (sorry, First Order) is again building a Giant Killing Thing to wipe out Mostly Innocent People (because mustache-twirling EVIL, that’s why) and the political establishment (making them, ironically, the rebels!), but a plucky band of Rebels (sorry, Resistance Fighters) manages to destroy it through a combination of one person turning off the shields (sounds … familiar …) and a bombing run where the bombs have to hit a small target by flying low in a suicide run (sounds … really familiar …).

Oh, but wait. Did I mention that the early part of the film covers the political awakening of a young man who was just trying to do his job (and a girl stuck on a desert planet with big dreams and few opportunities to achieve them — like I said, Finn and Rey have a lot of Luke between them) when the evil of the First Order’s machinations drive them to grow up quick and make huge life changes they are surprisingly well-prepared for, all revolving around a droid that contains a hologram of plans that are vital to the Resistance in the struggle to fight the Sith-led villains? Oh, and there’s a Cantina scene with pilots that will take you off-world for a price (though happily, Han shoots nobody in this scene … this time, and a sage old person who has Anakin/Luke’s light saber?

Finn seems to be a crack shot when (and only when) he needs to be, Kylo Ren is strangely bad at using his powers judiciously (you’d think someone would have noticed this after all the damage he apparently does when angry), Rey appears to be an ace pilot for no reason at all, and has huge untapped Force powers that emerge almost the minute she learns that the Force actually exists that allow her to be as world-class Jedi as a fully-trained Luke within a day, Han Solo just happens to be orbiting the very planet where the Millennium Falcon just happens to be sitting undisguised in the largest town (and Han is aware of the person who has it!), and though it hasn’t flown “in years,” it works more-or-less perfectly and somehow wasn’t destroyed by the First Order … oh dear, really I could go on like this for another few thousand words (and I am not kidding at all) on the silly contrivances that take careful observers out of the movie and into eye-rolling territory.

There’s a lot I’ll forgive in the name of fun, but there does come a point where you say OH COME ON!, and I should make clear that this is not the only movie I feel this way about: I’m not one of those people who get angry that we can hear sounds (like explosions) in space (where you actually couldn’t), but I do find that the utterly impossible physics in Peter Jackson’s films that can’t be hand-waved away by saying its a fantasy world (they’re all fantasy worlds, that’s why we call them movies, kids) really hurt the later Lord of the Rings movies, and in particular The Hobbit (as much as the stretched-too-thin storyline in the latter trilogy), the ridiculous stunts in the JJ Star Trek movies (of course you can fall many miles from a starship to a planet without being harmed! Of course you can be shot out of a photon cannon without a scratch!) really get to a point of ridiculousness where it takes me out of the movie, and that’s really annoying — like a fly buzzing around when you are trying to read a really good book.

I was really a lot more fearful for the JJ-led Star Wars going into it, and relieved this wasn’t as awful as Into Darkness, which I’m going to credit, unfairly and entirely, to Lawrence Kasdan. Kasdan’s no Harve Bennett, mind you, but he is generally a force for good story sense. It’s a pity he didn’t write this screenplay outright.

So, at this point let’s agree that The Force Awakens, um, borrows too heavily from A New Hope, and that this means things get awkward if we want to view Star Wars as an (in)complete saga. Unforgiveable? Maybe not, though we are left at the end of this movie with a setup that harkens back to the second chronological Star Wars movie so much that Episode VIII might end up being called The Emp — I mean, First Order Strikes Back: a young person who is strong in the force and has no immediate family we know about has left their old life behind, and arrived on a lush green world to be trained by a long-exiled Jedi Master, meanwhile the leader of the evil forces will plot revenge with his miraculously-saved apprentice, and the weakened Resistance will bravely fight the forces of the Empire (ack, sorry again, First Order), despite feeling the loss of a major character, who was murdered by the film’s chief antagonist.

I hope I’m wrong about Episode VIII, but come on, where else would a remake of A New Hope leave us? I actually love it when later films in a series “call back” to earlier films, but this is just way, too much. I would remind you also that I haven’t even gotten to some of the big, obvious (at least to me) issues or just plain dumb moments in the film: let’s take one just for starters — at the point where Snoke asks Hux to go get Kylo Ren, there is no possible way, even in Convenient Movie Time Stretching, for them to locate him, rescue him, and get him off-world in time. Rey’s rescue was a Lucky Coincidence too, but at least we saw them starting to go after her well before they reach her.

Yet, we know for sure that Kylo Ren will somehow be in the next movie, and now will need that mask he was conveniently wearing for no reason at all for reals. I’m hoping that if they go down this road, we get us some more Lando Calrissian. DO NOT go all Creed on me here, JJ — I demand 100 percent authentic Billy Dee Williams! If you’re going to remake Episode V, then I want Bespin and Lando and a Kylo Ren trap where they have to have an awkward family dinner, god dammit!

Speaking of Kylo Ren — why does he use the Force against nearly everyone except Finn? He knew something was up with Finn (FN-2187) early on — he noticed the trooper’s change of heart remotely, and knew it was him that helped Po escape. He has a lightsabre battle with Finn, but not only can he not beat him (even though Finn has never used a lightsaber in his life and is not very good with it), he doesn’t even really try to use any of the control tricks he used on Rey. Incidentally, Rey can speak Wookie, and droid, and at least one other language (when she yells at the scavenger who initially captures BB-8). The fact that she can speak droid might be explainable, but Wookie? Which doesn’t surprise anyone, like say Chewbacca or Han Solo, at all?

Finn, who worked with droids all the time as a Death Planet janitor, can’t speak droid. Nor can a lot of people in this movie, except Rey. If this doesn’t prove she’s Luke’s daughter, I don’t know what to tell you. There’s a number of other subtle and not-so-subtle hints that this may be the case; when we first see her, she’s dressed exactly how George Lucas and original Star Wars concept artist Ralph McQuarrie envisaged Luke looking when they were (briefly) considering making the character female, just as an example. Oh, and also, are there really only three kinds of planets: desert worlds, lush green planets, and permanent-winter hollowed-out Starkillers? How boringly familiar.

When she touches Luke’s lightsaber (get your mind out of the gutter, you pigs!), she hears voices, including a bit of Yoda and more clearly Obi-Wan Kenobi (voiced by Ewan McGregor, in a nice touch). That lightsaber, or lightsabre if you’re British, was unguarded and unprotected in a chest that looks similar to the one seen in A New Hope, and if you remember the films was actually lost when Luke lost his hand near the end of Empire Strikes Back. It fell to the bottom of the cloud city, so who could have retrieved it and brought it back for safekeeping? GEE I WONDER.

Like I said, there are a number of questions the film raises that could be addressed later, so I’m not going to belabor every one of them, but I do have to wonder about what kind of warped comment on solar energy it is when the Starkiller base (which actually kills planets, but never mind) depends on sucking dry the energy of a sun (which the planet could not possibly hold, but again — let it go). Indeed, when you think about it, that’s really all the weapon had to do: without a sun, every planet in that solar system will rapidly die, no PEW PEW PEW missiles of death needed. If our sun went out, Earth would become uninhabited in about a day, at most.

Other than for plot-mystery reasons, why can’t Rey remember her family? She just remembers them leaving, and being placed in Unkar Plutt’s (!) care (shades of Oliver Twist here, really …). She claims she “couldn’t imagine” a world as lush and green as the first one she gets taken to after leaving Jakku, but Kylo Ren noted that she dreams of exactly such a world, so … and while we’re at it, Leia appears to either know or intuitively understand who she really is (she just met Rey, but lets her be the one to go find Luke), but says nothing to her … presumably for only plot-reveal reasons later. That’s fine to a point, but it will look silly later if I’m even half-right about this.

I’m actually being easier on this film than it deserves — there are a lot more oddities/belief-stretching coincidences/“oh come on!” moments that I’m willing to defer since this is the first film of a new trilogy. There will be a lot of people who might read this and say I’m taking it too seriously, that Star Wars is meant to be nothing more than light adventure, and that there’s a lot of boom and wheee and pewpewpew and zoom, whiz, lightsaber sound effect and droid squawk, and that’s all anybody other that dorky nerds want out of it. Fair enough.

The problem is that Lucas and Kasdan and the writers since then have (well, for the most part) infused a rich backstory into what is more obviously shown on screen, one that intrigues and rewards looking deeper into the films, and that it really wouldn’t have hurt The Force Awakens to get that stuff right — almost every issue I’ve raised with the film could have been avoided with a single line of dialogue in the right spot. Another issue is that in trying to pay homage to the classic three films (Episode IV, V, and VI), Abrams is just unbelievably unoriginal and ham-fisted about it.

You want proof? Okay, let’s forget, for a moment, that The Force Awakens is very nearly a remake of A New Hope. Let’s forget that the Millennium Falcon has been lost for a dozen or more years, but gets found roughly five minutes after it is fired up for the first time in “ages.” Let’s forget that BB-8 is just another R2-D2, and that it’s still odd that with all that advanced science around, nobody seems to be able to make small droids speak English. Indeed, let’s doubly forget that at least 25 in-movie years have passed since the events of Episode VI — presuming Rey is Luke’s daughter, and looks to be in her 20s, and Kylo Ren looks to be not much older than that — and yet the technology for ships, blasters, stormtroopers, et cetera does not seem to have changed even a little from 1977. Put that all out of your mind.

There’s a moment where Finn bumps the chess table on board the Falcon, and the chess game turns back on. In the original film, this was a cute moment — and a tip of the hat to stop-motion special effects master Ray Harryhausen, who had just a few years earlier done some masterful work in the Sinbad movies. In the new film, the game picks up exactly where it was left at least 25 in-movie years earlier. Does that seem credible to you, given that the Falcon was acknowledged in the film to have been owned by several different beings, and looks to have been on many different adventures since Episode VI? There — that’s the whole problem with this film in a nutshell. It’s fun, it’s flashy, it’s exciting, but it is really not too credible.

Once again, JJ Abrams delivers enough bangpow to enthrall audiences, but the moment you stop and think it through a bit — you realize you’ve been had. This is a pastiche of the old films, not a new chapter in the story at all. The man doesn’t seem to be able to come up with a sensible original story to save his life, and when he thinks to go the safer route of remaking an old story, he mishandles it.

I’m relieved that someone else will be directing Episode VIII, because I don’t think this franchise could handle another Abrams hack job. I actually do care about this story; that’s why it disappoints me that we didn’t move the needle much forward, particularly with such a great cast and some lovely new ideas. So much more could have been done, but someone — either Abrams, or someone higher up at Disney — felt like a rehash of the one that had the big impact the first time around would be a better approach. This is just plain old lazy storytelling.

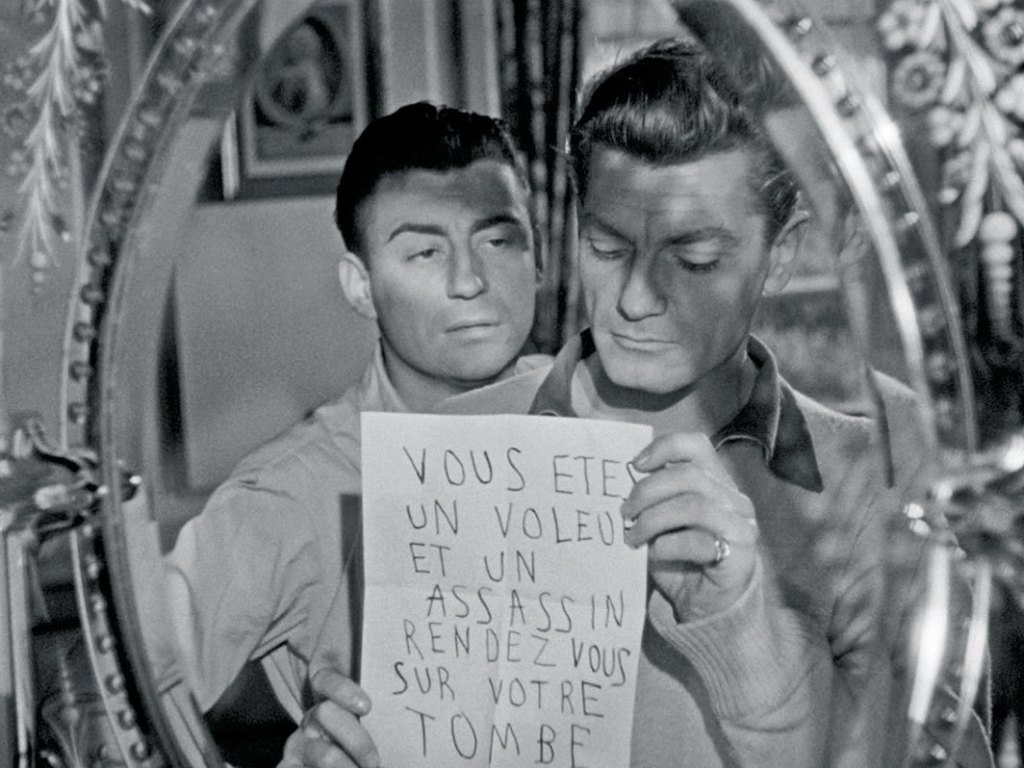

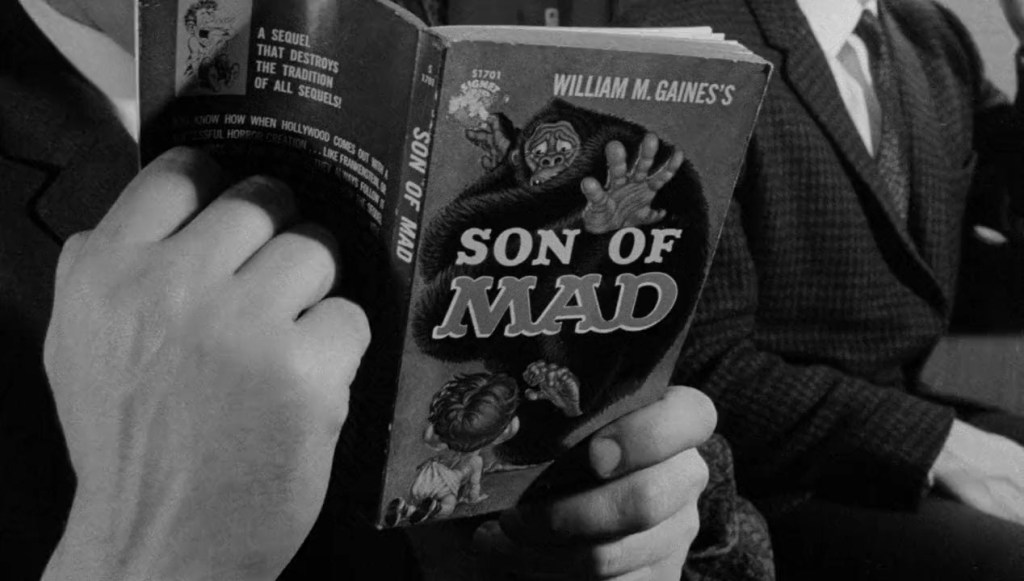

(Above: who is “The Pilot?” Did you see this in the film? Is he important? Nope, just more merch for you suckers to buy! Buy buy buy!)

Sure, they’ll make a gajillion dollars, and maybe that’s all that matters — there are more merchandise characters than actually appear in this movie, and some that do appear as toys would have you believe are far more important to the film than they turn out (at least so far) to be, and maybe that tells you something about where the creative energy in this project was really directed. I’m sorry to have to say it, but The Force Awakens is the movie equivalent of reality TV — visually appealing, popular, and fun — but kind of empty and unsatisfying, and not very good for your brain in the end.

Still, let it be said that the next related movie we’ll see — Rogue One — takes a different approach to working with what’s come before that could be quite interesting, and perhaps Episode VIII will finally take us someplace both new and complementary to the bold, brash, come-from-nowhere experimentation and energy that powered the first, and particularly the second, of the original movies. That’s my “new hope,” if you will.

To the extent that The Force Awakens is better-made than the Prequels, I am glad. To the extent that most people will find it thrilling fun that deeper subtext doesn’t matter to them, I am glad. To the extent that we still have a hope of getting a kick-ass chapter the likes of The Empire Strikes Back, I am glad and hopeful. Why, with so many great people working on this film, we couldn’t have gotten a torch-passing film that embraced the big dreams of the original classics instead of a remixed pastiche (that often wandered into parody … “you can always blow these things up!”), I am mystified. Playing it safe is the very last thing you should do with Star Wars.