⭐️⭐️⭐️

52-week film challenge, film 38

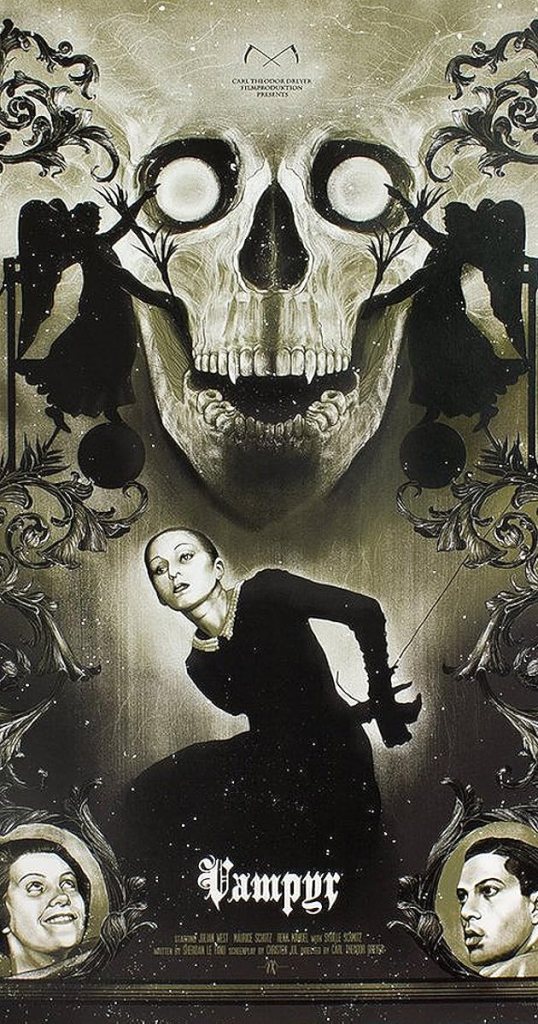

This film is a bit bewildering to me, I must confess. Taken as a filmic version of a horror-based dream (its clear intention), a reflection on some of the many tropes surrounding our own fear of our mortality and the ways we might depart this life, Vampyr should be considered a powerful success. If one is watching the film hoping for a coherent plot or definitive statement of meaning, you’re completely out of luck.

Given the utter brilliance of Dreyer’s previous film, 1928’s The Passion of Joan of Arc, his first sound movie — a horror movie about vampires — should have been a massive success.

Instead, it was a huge flop with audiences at first, and even after re-editing only garnered mixed reviews. This appears to be down to two main factors: his comfort in shooting movies in the silent style, along with unexpected struggles with adding sound (beyond music) to his film was the first problem.

The second “flaw” of a sort was his decision to make a dreamy, soft-focus, motivation-less tale dependent on atmosphere and imagery rather than story. Vampyr is 90 percent a silent movie, shot in that style, complete with title cards to explain things some (not enough) things from time to time.

The acting, likewise, is very silent-movie style, with few characters having much of anything to say on the rare occasions that they do speak. That said, there is some spoken dialogue and sound effects, which kind of gain a Bergman-like weight by their rarity.

The plot, such as it is: a man named Allan Gray, who is introduced as a dreamer who is obsessed with the occult to the point where he lives in a sort of dream state comes to a town, takes a room at the inn, where a man breaks in and leaves him a book “in the event of my death.” Shadows and instinct guide him to the manor of the man, who is murdered by a shadow with a rifle (?) shortly after Gray’s arrival.

He rushes to help, but it is too late. He meets the man’s youngest daughter, Gisèle, who says that her older sister, Léone, is gravely ill. Just then, they see Léone walking outside.

As they rush out to collect her, she is found with fresh bite marks and a briefly-glimpsed older person who quickly disappears. They carry Léone inside, Gray remembers the book, and starts to read it (there’s a lot of reading this book in the film).

Turns out it’s a book about vampyrs and their powers, which leads Gray to conclude (duh) that Léone is the victim of a vampire. A very odd and suspicious local doctor shows up, looking for all the world like Mark Twain.

The doctor says Léone can only be saved by donated blood, and arranges for Gray to provide some. Tired afterwards, he falls asleep.

One of the servants of the house reads Gray’s book, figures out what is going on, and knows who the Vampyr must be. Gray wakes up, senses danger, and saves Léone from being poisoned by the doctor, who may or may not have been trying to prevent her becoming a Vampyr.

Gray tries to catch the fleeing doctor, who may be a servant of the Vampyr, but stops to rest and has an out-of-body experience where he has died and is about to be buried by Marguerite Chopin (the Vampyr he saw earlier) and the doctor, confirming their alliance (maybe). As he returns to his body, he sees the old servant heading to the graveyard, and accompanies him.

They open the grave of Marguerite Chopin, finding her perfectly preserved. They drive an iron bar through her heart, and she dies a true death, instantly becoming a skeleton.

Léone is released from the curse, the doctor suddenly sees the face of the late lord of the manor, chasing him away from the house and killing the soldier who was helping him (?). Gray rescues the tied up Gisèle (?), while the doctor hides in the old mill, somehow becoming trapped in a grain bin.

The old servant shows up and turns on the mill, eventually burying the doctor in grain. Gisèle, who is apparently now in love with the nearly-silent Gray, leaves with him on a boat across the river and they find a bright clearing. The end.

For a sound movie, very little is said, and the interstitial titles give us a little background but avoid explaining much of anything as the story progresses. As mentioned, Dreyer opted to film this like a dream — complete with putting gauze near the lens of the camera for all the outdoor shots.

It’s very clear that he intended this to be a silent film, and was coerced to adding sound and really struggled with that. Thankfully, his next film, Day of Wrath (1943), received better reviews and largely found him back on course.

If you want a film that will weird you out, this might be a good candidate. Lots of gorgeous shots and symbolism give it a very disconnected dream-like effect, and I’m of little doubt that this film had a profound effect on David Lynch.

That said, the overall impression is that it’s half a movie: the visuals are there, but the storytelling is severely lacking. Even worse, the “hero” (or maybe more accurately, the “subject”) of the film, Allan Gray, is a nondescript nobody who spends the entire first half silently reacting to things, and leaving little impression on anyone but Gisèle, inexplicably.

He’s not even the hero; the old servant, who we don’t even meet until halfway through the film, is the one who actually resolves things — almost as though he was waiting for Allan to do it, gave up, and decided to end the movie as quickly as possible.

I’ve given it three stars because the visuals are ahead of their time, artistically interesting, and communicate the dream-like intention extremely well. Once people stop reading books and actually start doing things, the film really picks up — but even though the film is just 73 minutes long, the first half is an awful slog of odd things happening for no reason and an ineffective subject.

To put this another way: you’d never guess this was directed by the genius that gave us The Passion and the smaller masterpiece Gertrud, his final film. Vampyr feels more like an ambitious art-college experimental film.