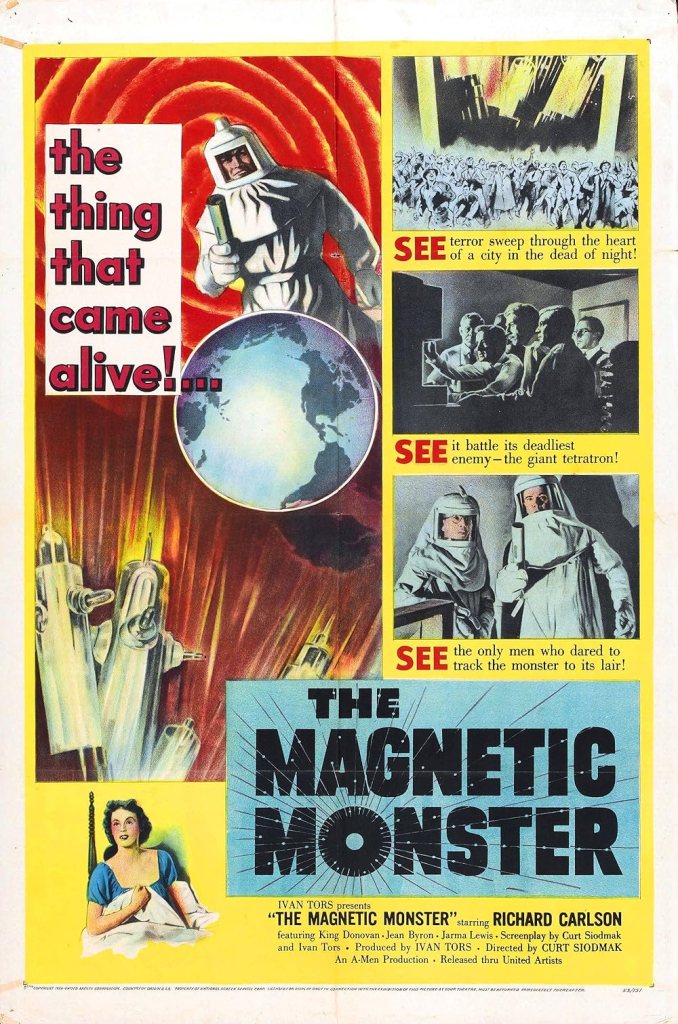

dirs. Curt Siodmak and Herbert L. Strock

⭐️⭐️⭐️

52-week film challenge, film 51

Despite some laughably bad science in much of it, no actual monster in the traditional sense of the term, and an effects-heavy climactic scene borrowed from another movie entirely, this Atomic Age film ends up being better (and surprisingly suspenseful) than you’d expect.

In 1953, America’s veterans had returned home, and the country had collectively forged a new direction: confident, industrious, lots of new inexpensive housing, the GI bill to get college-educated or trade-skilled, and basically hope for a bright future for nearly everyone. That said, there was the shadow of the coming nuclear arms race, and an understanding that scientific exploration isn’t always for the betterment of mankind.

That’s the mindset needed to better understand this picture, the first of a trilogy (!) of adventures involving the Office of Scientific Investigation (OSI), a group of scientists who investigate possible irresponsible uses of … SCIENCE! (Cue Thomas Dolby music here). Richard Carlson, also seen in It Came From Outer Space and many other cult pictures, stars as Dr Jeff Stewart.

His partner in this one is Dr Dan Forbes (King Donovan, another fantasty-film actor), and the first half of this film is basically a more-scientific police procedural — there’s a business in town that suddenly has all kinds of weird things happening, specifically things getting magnetised (as we quickly find out). The effect appears to be coming from a flat above the magnetised store, but by the time they work this out, the “culprit” has fled the scene, taking whatever it was that was causing this with them.

The sub-plot, such as it is, is that Stewart’s wife is pregnant but not showing (a constant source of conversation between them — “why aren’t you fat yet?” for example), and Stewart is inspired to buy a house for what he is sure will be a baby boy, but can barely afford it because apparently OSI officials are in it for the love of … SCIENCE! Bonus points for a now-hilarious breakdown of what it will take to buy a house in the early 50s on their basic budget.

Drawn-out story short, Stewart and Forbes track down an irresponsible scientist, Dr Howard Denker (Leonard Mudie) who was fooling around with making unstable elements and accidentally created a whopper — a radioactive isotope that, every 11 hours, uses magnetism to create energy from every available source in order to double its mass. While the problematic element is still small enough to fit in a briefcase, its exponential needs and growth means it will very quickly become a huge problem that threatens to destroy Earth, aka uncontained nuclear fusion.

Stewart and Forbes confront Dr Denker, who has brought this element on board a commercial plane (!) to try and get it to a university in California to make it their problem to solve, as he is dying from radiation poisoning. Literally in his dying breaths, Denker absolves himself from any responsibility for creating this world-eating thing, saying that he wasn’t responsible for the consequences of his experimentation.

Thus, the second half of the movie is a race against time. Even though the element is still of a size that is portable, it will continue to cause havoc every 11 hours when it needs to be “fed” — and its appetite is also exponetionally growing. The OSI convinces the town to undergo a blackout so that all available electricity can be diverted to the next “feeding” of the element so as to minimize the consequences — but now they have 11 hours until this thing is going to need 600 million watts of power for its next “meal.”

Stewart consults with various other scientists (more doctors per square inch in this movie than any other I can think of!) and eventually comes up with a theory: if he “over feeds” the element, it should split up into two stable elements, ending the threat to earth. But where to get that kind of power?

A US general blabs about a top-secret energy facility deep underground off the coast of Nova Scotia in Canada, and can provide the 600 million watts, but may not be able to be pushed much beyond that. Stewart and Forbes take the risk, fly as quickly as possible to the base, and make it just in time for the start of the magnetisation cycle that starts the “feeding” frenzy of energy collection.

The underground base and its magnetron/cycletron (not sure) are huge and impressive — and come from another movie, the 1934 silent German film Gold, very much in the mold of Metropolis’ special effects. Nearly-seamless editing puts Stewart at the controls of the machine as he pushes it well beyond its tolerances to “overfeed” the element, eventually causing the machine’s destruction — and a few tense moments of magnetisation where Stewart — who has barely escaped with his life — thinks he may have failed, and the world is doomed.

Happily, the magnetised things suddenly fall off the walls, and Earth is saved. The taxpayers of Canada are on the hook for replacing a now-dead power station, but let’s not talk about that! Quick, back to domestic bliss, patronising sexism, and house-buying!

Despite the all-over-the-place levels of scientific credibility, The Magnetic Monster is actually a surprisingly gripping film that holds audience suspense, still. It’s that 1950s earnestness of “we can do anything” spirit that foreshadows the space program and other great accomplishments of the following decades, I think, but it still works.