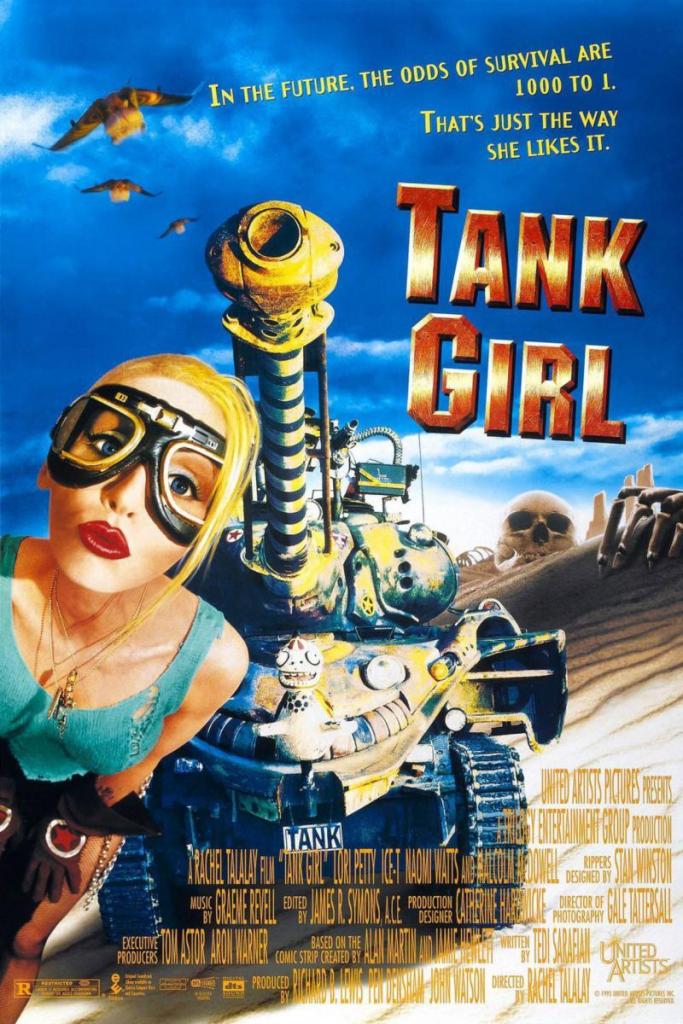

dir. Rachel Talalay

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

52-week film challenge, film 49

This review has to come with three disclaimers:

- I have never read the “Tank Girl” comic (though it looks like something I’d enjoy). I am reviewing the film strictly as a movie.

- I have met and chatted with the director, Rachael Talalay, about her career, US-Canadian immigration issues, and more recently I was present in Chicago for the debut of her latest bit of TV work (for Doctor Who, as it happens), but this doesn’t influence the review too much.

- I am aware that the film was, in parts, heavily re-edited by the studio.

With that out of the way, let’s dive in.

Hoo boy, has Tank Girl ever aged well. On its original release, it didn’t do well financially, though it later earned cult status on the strength of its strong “feminist futurism” and humour. It is almost, but not quite, a mirror-universe version of 1984’s The Adventures of Buckaroo Bonzai Across the Eighth Dimension, only with far fewer goatees and more mutants, who eventually form an alliance to take down the mad big bad (Malcolm McDowell, in this case).

Like the earlier film, it has a definite aesthetic that reflects the decade in which it was made, is funny but not meant as a parody, and does some excellent world-building that pays homage to its influences. In the case of Tank Girl, the world of 2033 looks increasingly likely to come to pass — only instead of a comet directly hitting earth causing the climate to change, we just have man-made climate change. I can see this “future” from my house, so to speak.

A hasty voiceover from yet-to-be Tank Girl herself (Lori Petty) sets up the story: since the comet hit (presumably with enough force to push the earth closer to the sun), it hasn’t rained in 11 years, and the world has mostly turned to desert. The (male) elites have taken control of the enormous reservoirs of water underneath the sands in the only livable area left (the former Australia), thus controlling nearly all of the remaining population.

Some Mad-Maxian-type rebels live “free” in the outback in a commune, relying on finding and tapping into parts of the reservoir to survive. Although the head of the monopolistic Water & Power Corporation, Kesslee (McDowell), is trying to find and destroy these water pirates, the rebels fear another enemy much more: The Rippers, who are kind of armored super-soldiers operating from a secret base.

The Rippers attack both W&P and occasionally the rebels under cover of darkness. Insert your own analogy to the aboriginal native populations of various countries (and of course capitalism) right here.

W&P discover the last well the commune has tapped, and attack the commune (which is decorated like every 90s teen’s dream) with corporation troops, killing many of the rebels. The body count includes Rebecca Buck’s (Petty) boyfriend Richard (Brian Wimmer) and, after a brave fight, capturing Buck and a young girl from the commune named Sam (Stacy Linn Ramsower).

In a classic trope, Kesslee is fascinated by Buck’s spunk and sarcasm — and instead of just killing her, instead enslaves her. When she continues to rebel, he subjects her to various tortures.

Buck meets a fellow prisoner, who Buck nicknames Jet Girl (Naomi Watts) because she is being used as a jet mechanic by the cruel (read: rape-minded) troops. Jet Girl urges Buck not to fight back, but Buck is having none of it — and saves Jet Girl from a stalker trooper by pretending to be Jet Girl’s jealous girlfriend.

Kesslee decides to use the rebellious Buck to lure the Rippers out into the open, but the plan backfires, and Kesslee is gravely injured. Buck gets a tank (and is now Tank Girl), Jet Girl steals a jet, and they seek shelter and spend time modifying their weapons and plotting to break W&P’s control of the world’s water.

Their success prompts Kesslee to use the little girl Sam as both a hostage and bait, and puts the child in serious danger at one point — I don’t want to say more than that, but Iggy Pop is involved, and not in a good way. The Girls (Tank, Jet, and the little-seen Sub) get wind of this, and redouble their efforts.

The ladies form an alliance with the Rippers, who we discover are mutated men (and the occasional dog that was first mutated into a man) who have been fused with kangaroo DNA (because Australia!) into a funny-looking mercenary force originally created by W&P before being largely wiped out for rebelling. Kesslee hopes their united force will attack so that his army can crush them all, but things don’t quite go according to plan.

The film might possibly err a little too much on the comic side, but the look and set pieces are aesthetically pleasing throughout. As mentioned, looking at this almost 30 years after its initial release, it seems prescient and less unrealistic than it probably did in 1995. Indeed, “Kesslee” rhymes with “Nestle,” and if you don’t think that evil corporation isn’t trying to buy up as much of the fresh water supply as it can, you might want to read up on that topic.

In the meantime, the rise of women as role models, heroes, rebels, and the leads of non-drama films over the last three decades makes Tank Girl ever more relevant as the years go by. When it was first released, some critics and most audiences didn’t quite “get it,” but the tween/teen girls who got to see it took it into their hearts, and built a cult following around it.

The film turns out to have had enormous staying power as an influence, both outside and inside Hollywood. Although the film flopped in its theatrical run, it did okay with critics — and I think it has since garnered enough respect that a Blu-ray release beyond just the US would be justified.

If said Blu-ray could also include a ”restored” version that undid the watering-down cuts and edits the studio insisted on (among many other things, reducing Jet Girl and the blink-and-you’ll-miss-her Sub Girl’s roles, not to mention changing the ending), I think it could even be a hit on the revival circuit as well. As Ms. Talalay has gone on to a strong career in TV and film since then, I look forward to asking her about the “Kesslee” name, and the possibility of a “Director’s Cut,“ when next our paths cross.