⭐️⭐️⭐️½

Disney Studios

Director: Brian Henson

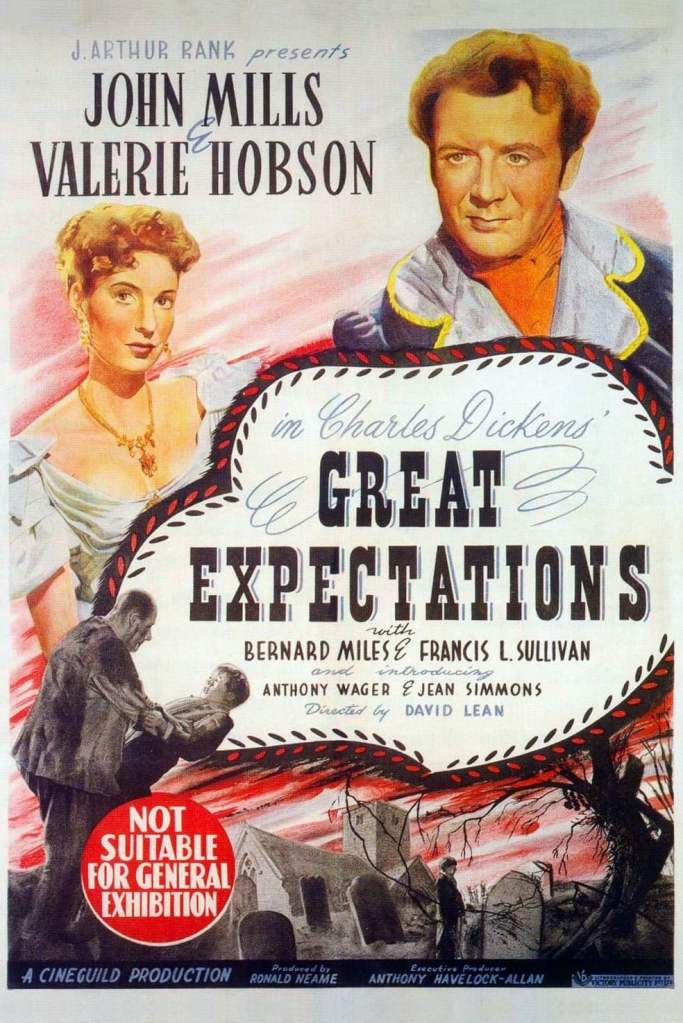

We have a Christmas tradition of what I think is the best version of “A Christmas Carol” ever committed to film, the 1951 Alastair Sim version (UK title: Scrooge, and my review of it is here). This year, just to do something a little different, we revisited The Muppet Christmas Carol after not having seen it since its 1992 theatrical debut, just to change things up a bit. The film sticks to the same story (more faithfully than Scrooge, in some ways), but approached the source material in an almost-completely different way: it’s a musical, for starters, and it only has two substantial speaking roles for human beings.

In short, this film is a technical marvel, and the overall story is well-executed — but Caine as Scrooge is curiously flat, and the songs (by Paul Williams) are both samey, and rather meh. I’d certainly recommend this one over my beloved 1951 version when it comes to “suitable for kids, grandparents, pets, and the whole family,” but while it scores well on some fronts, its general over-busyness, the decision to make it a musical, and the changes to the story probably won’t sit well with Dickens fans.

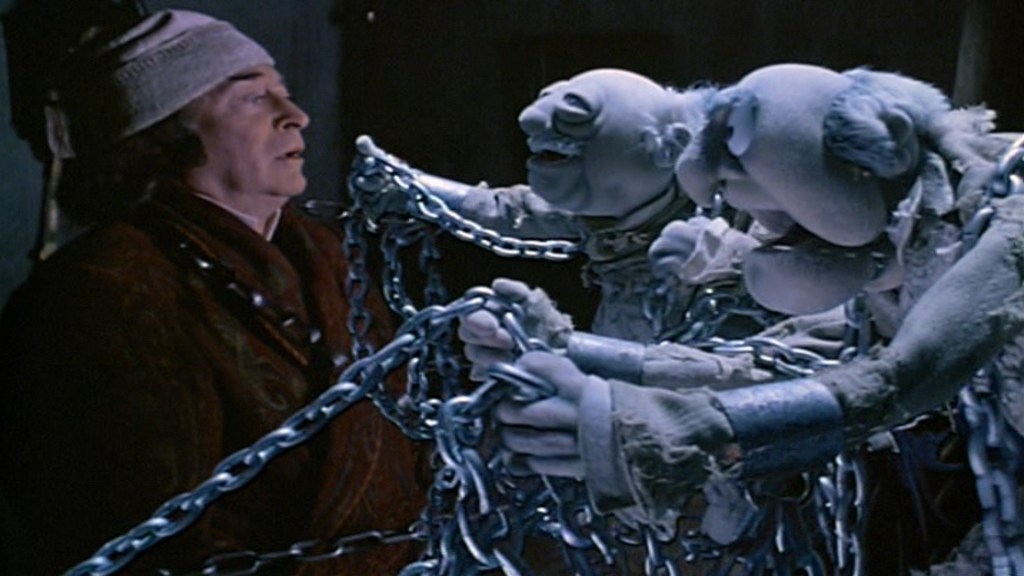

I’m not sure who’s to blame for Michael Caine’s mostly-lifeless portrayal of Scrooge; director Brian Henson was of course focused on his muppets, and they uniformally shine here, so he may have decided that Scrooge’s inhumanity to his fellow man should be more low-key until his reformation. Or maybe Caine thought the movie was dumb, and did it for the paycheck (that’s certainly the vibe he gives off for the first two-thirds of the film).

For what it’s worth, I think the film would have worked better with maybe one big musical number at each end rather than making the whole thing a musical, since the songs are, to be frank, unmemorable and just fill time. The Muppets’ recasting into various roles from the story, on the other hand, works surprisingly well, with The Great Gonzo (Dave Goelz) as Charles Dickens (among many other roles) and Rizzo the Rat (Steve Whitmire, again also playing Kermit, Beaker, Bunsen Honeydew and a half-dozen other parts) serving as the Greek Chorus to Gonzo’s Dickens narration. Long-time Muppet veterans Jerry Nelson and Frank Oz take up their usual roles with wit and gusto, with David Rudman handling some minor roles and a cameo from the Swedish Chef.

When Scrooge is seen in flashbacks in the early parts of his life (Raymond Coulthard, Russell Martin, Theo Sanders, Kristopher Milnes, and Edward Sanders), the character is more “alive,” a trait Caine slowly picks up on during his ghostly visits, and finally brings to the fore at the very end. The other main human-being speaking role is Fred, Scrooge’s nephew, and actor Steve Mackintosh is just fine in the role, but should have been used elsewhere (we’ll come to that later).

A lot of respect must go to the muppet performers in the lead roles, who have decades of experience with these familiar characters and carry it off on a movie scale just as well as they do on television. Special respect must go to the muppet performers who play the ghosts: the floating and diminutive Ghost of Christmas Past (Karen Prell with voice by Jessica Fox), the giant Ghost of Christmas Present (Jerry Nelson and Donald Austen), and the effectively haunting Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come (Rob Tygner and Donald Austen).

There are also dozens of “little” Muppet characters (mice inside the homes, rats who work for Scrooge’s office, etc), and some giant characters, and the spirit of Jim Henson lives on in these parts and the talented people who bring them to life. In the finale, we get to see over 100 muppets in a panning shot, a very impressive accomplishment that makes them all the more “real” throughout much of the film.

It later came out that English actors David Hemings, Ron Moody and David Warner (the latter would have been my pick), alongside American comic George Carlin (who might also have been quite good) were considered for the role of Scrooge before Michael Caine finally won the role. I’m still not sure if Caine’s low-key misery was his choice or Henson’s, given that this is a family/kids version of the tale, but Caine noted that he based his portrayal on the present-day vultures of Wall Street and the banks, which may account for the more bloodless, cynical portrayal.

The “London street set” used in the film was uncannily similar to the one used in the 1951 Scrooge — modified for scale, obviously — which delighted me, but while I understand the decision to keep the Muppet characters the audience would know using their original voices, the lack of UK accents from nearly everyone apart from Mackintosh and Caine was a disappointment to me, especially for the Ghosts. Given that the story, author, characters, and filming location were all in the UK, I felt like every character (with the Swedish Chef obviously exempt) should have added a UK lilt to their voices.

I haven’t mentioned Kermit the Frog as Bob Cratchit thus far in the film, for two reasons: first, although Bob is the raison d’etre of Scrooge’s reformation, he’s hardly in the film; and two, he doesn’t really communicate Cratchit’s plight because Kermit is a good-natured, happy frog at heart and is incapable of portraying suffering. I can’t believe I’m saying this, but Kermit was badly miscast, and should have played nephew Fred — while Steve Mackintosh, who played Fred, should have played Bob.

Nitpicking aside, the film does carry a lot of family-friendly humour, and succeeds in reforming Scrooge and being generally heartwarming. It’ll never replace Scrooge for me, but that said it is also nowhere near the worst version of A Christmas Carol committed to film. As a first version for kids to see that might get them interested in the story and other film versions, it’s fine.

The one high mark I will give this version is that, despite the musicality and comedy inherent in it, it does not shy away from painting the capitalist banking system as morally bankrupt and preying on poor people — the point of Dickens’ original tale in the first place, so good on them for that.

There’s a moment where Sam the Eagle, the All-American type, gets corrected in scene that this is a British story, and does a retake correcting “the American Way” to “the British Way” that I found quite amusing. On the whole, it’s a classic aimed at the smols in your household, it’s cute, it’s fun. There’s an extended version of the movie that restores one cut song, but don’t bother with that — one more song is exactly what this movie didn’t need.