Director: Shinya Tsukamoto

⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

If you’ve seen this film, there’s not a lot I can say apart from some small bits of trivia that you might not already know. If you haven’t seen it, this is the first and perhaps the greatest Japanese cyberpunk/body horror/indie metal/sex comedy film of all time. I haven’t seen either of the two sequels, but that’s the only reason I say “perhaps.”

Perfectly timed with a youth-cultural rising tide of nihilism, low-budget renegade filmmaking, steampunk fashion, and the emergence of “industrial” music, Tetsuo combines it all into a movie that was very much of its moment. I first saw the film at and independent cinema in central Florida a few months after it premiered, and I was simply not prepared for the onslaught of sight and sound I witnessed.

It was in some ways traumatic, in other ways compelling — and it haunted me for a while with a mixture of revulsion and wonder at the time. I have finally dared to take a second look, and I squirmed in places — but could still could hardly bear to blink.

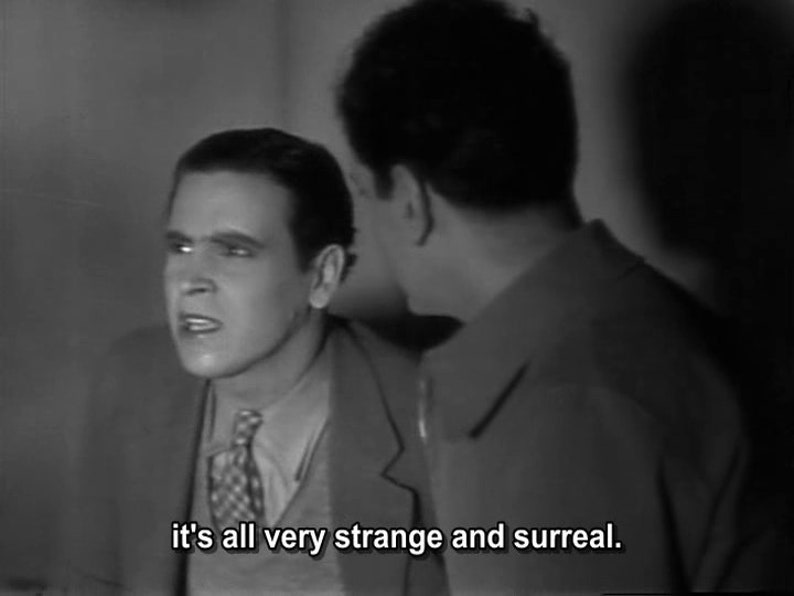

The film is in B&W, and doesn’t look quite as absurdly cheap as it is most of the time thanks to ludicrously frenetic stop-motion effects, brilliant editing, and mesmerizing performances, while still mostly giving its audiences only glimpses of what’s fully happening. The assault of hard music contributes to the urgency and raw emotions on display throughout.

The film went on to be an enormous influence on both musicians and indie directors, and makes those Godzilla movies look like pastoral landscape paintings for children by comparison.

The plot is weird yet simple: we start with meeting a young man (played by director Tsukamoto) who is cutting his thigh open so he can insert some metal into it. His surroundings are composed of lots of scrap metal, and this is a fetish of his apparently.

It goes very wrong, and maggots begin to feed on the wound. Driven mad with disgust, he runs out of his tiny room and into the night, and is soon run down by a “salaryman” (businessman) — played by Tomorowo Taguchi — and his girlfriend (Kei Fujiwara).

The pair investigate the corpse, are revolted, and dispose of the body. Not long after, the businessman notices that he is growing metal out of his body, and soon the girlfriend is transmuting as well.

Slowly but surely the metal is taking over their bodies (mostly done using stop-motion animation), turning them both into metal-human hybrids. This takes a while, and is documented in beautiful detail in the grainy B&W cinema verité style, augmented with the hardened edges of industrial music.

Once it starts, it is a relentless onslaught, and the victims here are bewildered, terrified, and powerless to stop it.

To this point, the film is a hyperactive low-budget body horror escapade, but strangely compelling. We know where this story is going, but it is clever enough to make us want to see it through.

The salaryman’s transformation is much further along by the time the girlfriend turns up, equally starting to transform. They end up being compelled to have what I’ll just call “drillsex,” which at this point provides a much-needed moment of relative levity.

Others have described the film as something of a mash-up between Un Chien Andalou (1925), Videodrome (1983), and Eraserhead (1977) in Japan, and I have to nod and say “yes, but with all these films thrown in a blender while you’re watching them.” Tetsuo vibrates with energy and intensity, never relents from its breakneck pace, and cranks the music up to 11.

Since it’s release, we’ve all started down its path: rare is the moment now where you don’t see someone glued to their smartphone, to the point where we treat it as an extension of “ourselves.” The messages of the film regarding societal sexual repression, industrialized alienation, body dysmorphia, work-life imbalance, and are alternately sublimated and beaten over your head.

Being so hyperkinetic and, well, metal is likely to be overwhelming for any casual viewer, even though the film clocks in at a mere 67 minutes (and thank heavens its not any longer). By the end, you’re not sure if the salaryman and his girl likes what has ultimately become of them or not.

It reminds of a rollercoaster you’ve never been on before: terrifying, exhilarating, and you’re relieved you survived it — and then, knowing that you did, you want to go back and do it again.

Tsukamoto served as writer, director, producer, art director, lighting director cinematographer and editor of the film. A number of the other crew members who worked on the film quit in disgust or in dispute with what Tsukamoto was doing.

It is a visionary, hugely influential and eye-popping film in many ways, but I think most people whose idea of a horror movie is Friday the 13th would probably turn down a second opportunity to see it. That said, a little of that metal fetishism stays with you, in the sense that you can’t unsee it.