⭐️⭐️⭐️½

52-week film challenge, film 24

I had previously seen clips from this version of the story, but never saw the entire film until now. I have to say I like it a great deal less than the 1924 version with Douglas Fairbanks (Senior), but this first colour production was a huge technological achievement for its time, even though — what with the breakout of World War II, and no less than five directors, along with various other issues — this version is mostly successful at what it sets out to do, but is also a bit of a hot mess.

You have to respect the ground-breaking effects (including the first use of what is now called Chromakey), the brilliant sets, the beautiful location photography (a mix of London and California, the latter being used after the war broke out), the lovely set pieces, and the gorgeous three-strip Technicolour process. It won Academy Awards for cinematography, art direction, and special effects, and was nominated for its music (the latter by the great Miklós Rózsa after a false start by Oscar Straus).

Because of the various problems during production, original director Ludwig Berger and Berger’s choice of composer (Straus) were eventually replaced primarily by Michael Powell. Powell also had to leave the production before its completion due to the war, and American Tim Whelan directed nearly all of the latter half’s outdoor scenes in California with assistance from the Korda brothers. You can already see why the film, as entertaining and gorgeous as it turned out, doesn’t always hang together.

The story, which has also gone by the name Aladdin and variations thereof for many film versions, was first made into a film in 1905 and across the 20th century (and into the 21st, with Disney’s live action remake of its own 1992 animated Aladdin). The core story is often said to be drawn from the medieval collection of Middle Eastern tales known as One Thousand and One Nights, but this is somewhat inaccurate. The Aladdin tale specifically (along with the Ali Baba tales) was added to the collection from other sources by the 17th-century European translator of the tales, Antoine Galland.

Producer Alexander Korda was inspired to do this movie by the 1924 silent version, but changed the story pretty substantially — as just one example, making the thief and the King two separate characters. If you don’t know the 1924 version like I do, this is a mostly-successful telling that tries to combine some variations of the tale into a coherent whole, and mostly does it quite well.

It is certainly a fine family film with enough fantasy to hold its audience even now, though I’m very glad they changed direction from its intended “full blown musical” idea. Three songs are still in the film, but apart from Abu’s solo song, they don’t disrupt the story.

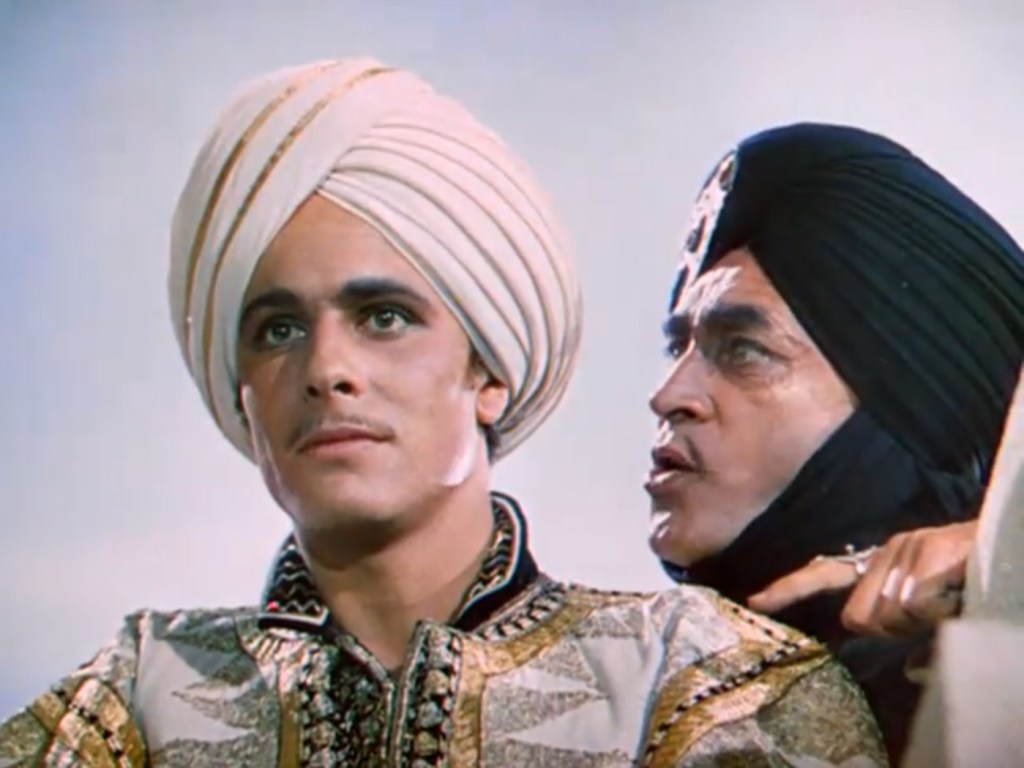

The film opens brilliantly, as a blind beggar in ancient Basra along with his faithful dog companion tells the first part of the film’s tale in flashback. He tells of a young and naive King Ahmad of “Bagdad” (John Justin), who wants to learn more about the people he rules, so he is persuaded to go undercover by his evil Grand Vizier, Jaffar ((the great Conrad Veidt, who completely steals every scene he’s in).

Once Ahmad is out of the castle and pretending to be a humble beggar, Jaffar has him arrested, and thrown in prison — later telling the people that Ahmad died, so Jaffar can claim the throne. Ahmad meets a young thief while in his cell called Abu (played by then 15-year-old Sabu Dastagir, who just went by “Sabu” in his film career).

Abu, a carefree youth, disbelieves his cell mate is the king at first, but befriends Ahmad — and pickpocketed the key to the cell so they could escape. They flee to Basra, where Ahmad spots the princess (June Duprez) and immediately falls in love with her. However, Jaffar is also in Basra and trying to win the Princess through other means — flattering her father, the Sultan (Miles Malleson, also one of the writers of the film), with life-size toys — the Sultan’s obsession. Malleson is another highlight, a wonderfully child-like old man played to perfection.

Jaffar seals the deal by giving the Sultan a mechanical flying horse, but in the meantime the princess and Ahmad have met, and the attraction is now mutual and she escapes the palace. Enraged, Jaffar uses his magical powers to blind Ahmad, and turn Abu into a dog. The princess is recaptured, but falls into “a deep sleep” and cannot be awakened.

Ahmad, still blind, is eventually tricked into returning to the palace, where he awakens the princess, and is then dismissed, along with his dog Abu. We return to the dock where we first met them, as he concludes his story — but the adventure quickly continues as the Princess is tricked into boarding Jaffar’s ship.

Now a prisoner, Jaffar tells her that his curses on Ahmad and Abu can only be lifted by her embracing him, which she very reluctantly does out of love for Ahmad. The spells are lifted, and Ahmad spots her and sets after the ship along with the now-human-again Abu. Jaffar sees them a bit later, and raises a storm that shipwrecks their small dinghy, then returns to Basra and uses a mechanical dancing goddess toy to kill the Sultan before returning to Baghdad.

Meanwhile, by sheer lucky coincidence, Abu finds a bottle on the deserted beach and opens it, revealing a very temperamental and gigantic genie (Rex Ingram). Ingram handles the role as best he can, but he’s just not very convincing — and the effects regarding the size differences between him and Abu, though imaginative, aren’t generally carried off well enough to continue the suspension of disbelief.

Still, the influence of this film on later filmmakers like Ray Harryhausen simply cannot be overstated — this is the blueprint he and others followed for decades to come when it came to imaginative tales of fantasy. In addition to Harryhausen, Terry Gilliam’s best films are also clearly influenced by this movie.

The genie helps Abu steal a magical jewel from a faraway temple (with a Keystone Kops-esque guard squad) that helps him find and reunite with Ahmad, all of which is really well done. Abu and Ahmad use the jewel to see Jaffar hypnotizing the Princess to forget her love for Ahmad, and our hero loses hope and angers Abu — until Abu accidentally uses his third and final wish to send Ahmad back to Baghdad.

Abu then breaks his giant jewel out of anger, which introduces a handy plot device to get him also back to Baghdad via a flying carpet (very well done compared to the flying horse effects), the appearance of which triggers the population into overthrowing Jaffar, who is then killed by Abu, restoring Ahmad to power and allowing him to marry the Princess, who never did get an actual name.

Abu is offered the position of Grand Vizier to King Ahmad, but shuns any form of responsibility, re-steals the flying carpet, and heads out to more adventure. Everyone laughs, and the film concludes happily. You can almost forget how bad Sabu’s song was (he was otherwise generally excellent).

In its day, the film was a wonder and did very well at the box office. It maintains a good reputation (now as a children’s movie) to this day.

This version of The Thief of Bagdad was the template for most future special-effects-heavy fantasy films for decades to come, largely due to Larry Butler’s invention of ChromaKey, which with some later polish became the successor to the “traveling matte” techniques used in prior films.

Viewed as an adult, the physical effects are mostly great — and while the Chromakey effects are often so obvious it takes you out of the film, the alterations to the tale and a few handy plot machinations do not. Watched bearing in mind its technological and historical importance, it is still enjoyable, and well worth the 108 minute runtime.