⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

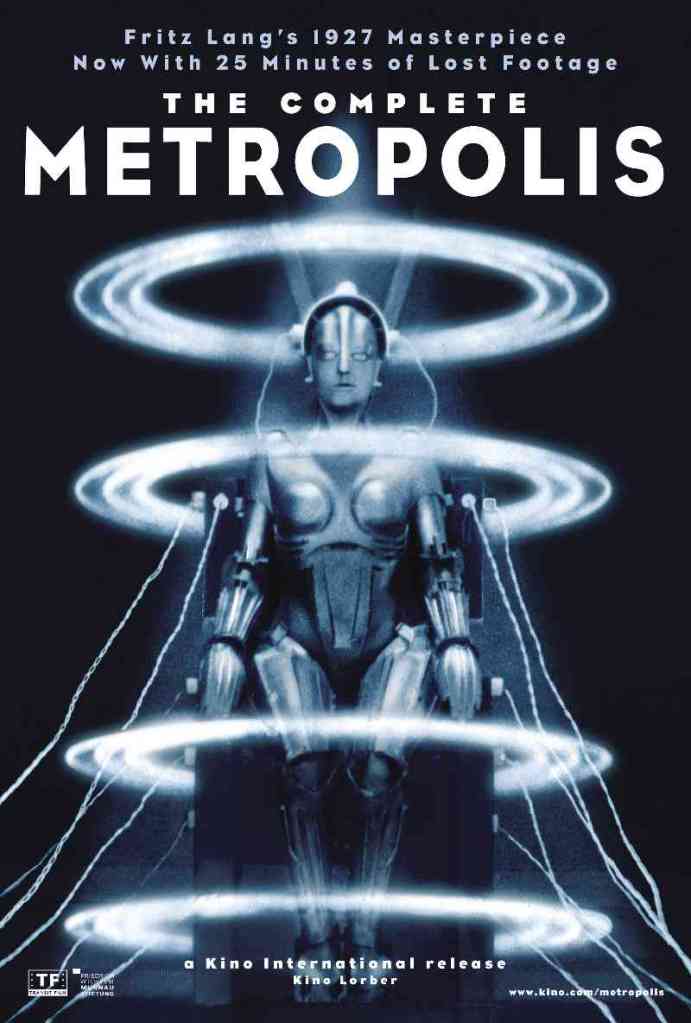

“Complete” version, 4K with restored scenes

52-week film challenge, film 18

Quite possibly the most visually compelling film ever made, even after nearly a century. Certainly the most beautiful silent movie ever made. I recently noticed that Criterion had a 4K copy of the 2010 “Complete” restoration, so I watched it to see what had been added since the 2001 version. It turns out that the answer is “about 24 minutes more story, and a new version of the original score,” but there’s more to it than that, of course.

Lest we get too far ahead of ourselves, and for those who’ve never watched the whole thing, Metropolis is an incredibly futuristic-looking silent movie that absolutely everyone on Earth should at some point see. The reason I say this is that it is truly one of the most incredible film productions ever made from a visual standpoint, and on top of that the storyline is (sadly) still very relevant today.

The effects may be primitive by comparison to today’s films, but Lang brought a style and credibility to them — complemented by the design and art direction of the non-FX scenes — that not only hasn’t dated it, but in fact plays a huge role in the film’s immortality. Parts of his vision are the sort of future we all hoped we’d grow up in, but the underside (literally and metaphorically) of this future projection are indeed the world most of us ended up in.

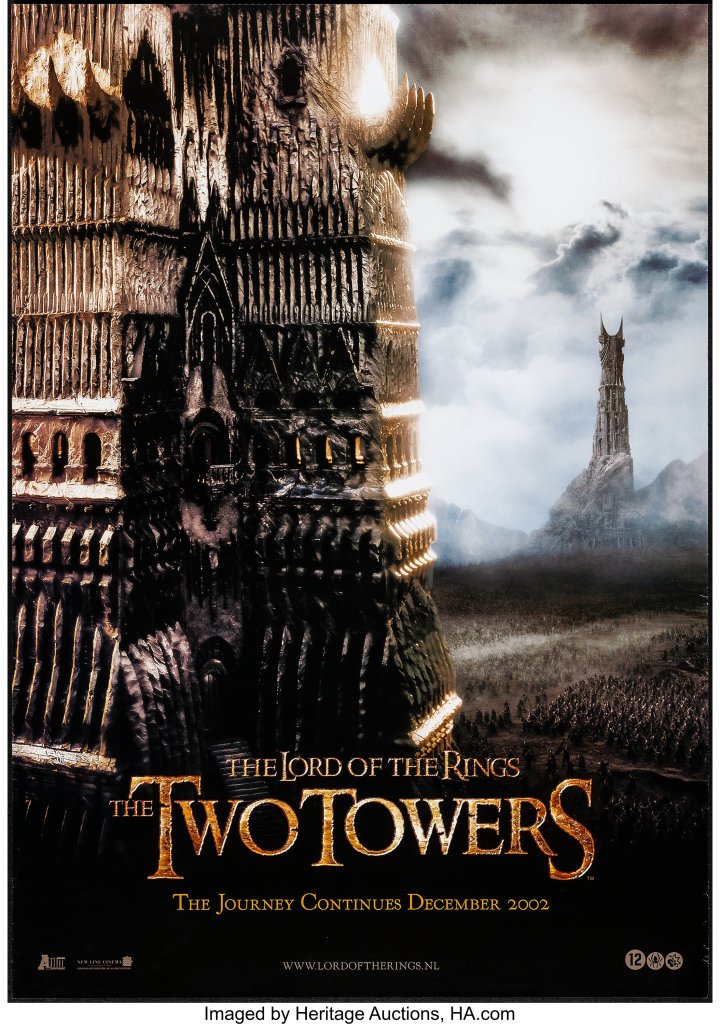

As the film opens, we gaze upon an incredibly modernism-influenced style cityscape dominated by an exceptionally tall, large, and distinctly Art Deco Tower of Babel, with trains and cars on elevated railways bustling along at various levels on and above the ground, with airplanes (well, biplanes — a rare example of a visual that didn’t age well) buzzing around. The top of the tower is where the Master of the City (a sort of architect/chief executive) Joh Frederson and his adult son, Freder, live and enjoy the hedonistic lifestyle of the city’s elites. Lang said the look was inspired by his first trip to New York City.

Although there is no direct reference in either Thea von Harbou’s original 1925 novel-as-film-treatment nor in Lang’s film as to the exact time period, a 60s reprint of the novel placed it firmly as set in the year 2026. Whichever editor came up with that pretty much nailed it, as we are currently living in world alarmingly similar to the one described in the source material.

Freder, as a member of the elite, spends his days in gardens and playing sport and other such idle leisure — hobnobbing with the business magnates and politically-powerful and blissfully ignorant of how it all works. Meanwhile, the working class who actually make the city what it is live and work underground in a very functionalist, expressionistic Worker’s City, and toil on keeping the machines that power the metropolis of the elites in scenes that “influenced” Charlie Chaplin for his 1936 film Modern Times.

One day, a a radical woman teacher dates to bring some of the workers’ children up to the gardens to see how their “brothers” live. Freder is struck by the woman, Maria, and follows her down into the Worker’s City, where Freder sees firsthand the impoverished working class and the soul-shattering labour required to provide the elites with their lifestyle.

Though it was meant to be a parable on the danger of power imbalances, regrettably the problems shown in Metropolis have reared their ugly heads once again in a number of countries that have recently seen class-based unrest and abuses of power by those in charge. Anywhere you find that the elites live a lifestyle completely removed from the majority (who are of course taken for granted as an endless cheap labour supply), you will find strong echoes of this film, which regrettably still feels relevant and relatable nearly 96 years after its release.

Freder catches up with Maria, who he discovers is a symbol of hope for the workers, and she predicts that a “mediator”-cum-saviour will someday appear to resolve the growing chasm between the workers and the elites. Having been traumatized by this disparity himself, Freder sees himself, as the son of the city’s Master, as someone who could fulfill that mediator role, and falls in love with Maria.

Trials and tribulations ensue, and in the secondary plot it is revealed that there is a “mad” scientist in the city, Rotwang, who seeks revenge on Joh Frederson because Rotwang’s love — a woman named Hel — left him to marry the rich/powerful Joh, giving Joh his son Freder before dying. Rotwang has built a mechanical “man” — an iconic and insanely Futurist (but unmistakably female) robot design that he has plans for.

Joh, upon learning of the robot, orders Rotwang to remodel the robot to look and act like Maria — the heroine of the workers — but to have it incite the workers into violence against him. Joh wants this so he can crack down and destroy this attempt at workers gaining negotiating power, but while pretending to follow the order, Rotwang schemes to use the Maria-bot to fulfill his own plans, which are to resurrect Hel and take his revenge upon Joh.

Skipping a lot of exposition, Rotwang’s plan works only too well — Maria-bot incites the workers into a rabid state and commands them to destroy the machines, which will in turn destroy the Metropolis and its elite class. This isn’t what Joh intended, and it has the side effect of destroying the Worker’s City through flooding. While the workers are revolting, the real Maria escapes and tries to save the workers’ children, left behind in the fever of revolt, before they all drown.

Freder finds Maria, and along with his close friend Josaphat manage (barely) to rescue the worker’s children, and eventually get word of this to the workers, who by now have thought they accidentally drowned their own children and were so wracked with grief that they capture the Maria-bot and burn her at the stake. Rotwang gets his comeuppance, Freder gets Maria, and Joh learns the error of his ways.

What’s great about this new version is that the extra footage — which sadly could not be fully restored and is quite distinct from the previously-upscaled footage — adds depth and nuance to the story. In particular, this “complete” version really fleshes out some of the seconddary plot and in particular the supporting characters, from Josaphat to the unnamed Thin Man to Georgy, a worker that Freder befriends and learns from, temporarily trading places with him so that Freder can experience the worker’s life, and Georgy gets to briefly be experience the elite life.

The wickedness of the Thin Man, Joh’s enforcer so he doesn’t have to get his hands dirty, is made much clearer in this version, as is the affectionate relationship of Josephat and Freder, though there is of course no hint of beyond a close friendship. It was nice to see that level of male bonding without sexual overtones for a change.

The film is now almost to the full running time Lang intended (two short scenes are still wholly missing, and captions are used to cover this), and while yes, its now even longer, it is still so fascinating that the 2.4 hour runtime just flies by. Barring some significant new discovery of a better print or those missing scenes, this is the most complete version we’re likely to ever get.

One can only hope that that perhaps the current “AI” fad will enable further restoration on the damaged but intact extra 24 minutes, making the switch between those scenes and the rest of the film less jarring. I could easily see how, at a minimum, the backgrounds could be extended to give those scenes the same 16:9 ratio as the rest of the film, and that would definitely be worth doing.

As I mentioned earlier, this is one of the incredibly few films that really should be seen by pretty much everyone everywhere. It is more than just a visually-captivating classic with a timeless message about the evils of exploitation; it is a plea to the future not to remake the mistakes of the past, which sadly has been ignored time and time again.